Cyberspace Blues

According to current scientific dogma, everything I experience is the result of electrical activity in my brain, and it should therefore be theoretically feasible to simulate an entire virtual world that I could not possibly distinguish from the ‘real’ world. Some brain scientists believe that in the not too distant future, we shall actually do such things. Well, maybe it has already been done—to you? For all you know, the year might be 2216 and you are a bored teenager immersed inside a ‘virtual world’ game that simulates the primitive and exciting world of the early twenty-first century. Once you acknowledge the mere feasibility of this scenario, mathematics leads you to a very scary conclusion: since there is only one real world, whereas the number of potential virtual worlds is infinite, the probability that you happen to inhabit the sole real world is almost zero.

—Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus: A History of Tomorrow

I expect there will be more virtual schools.

—Betsy DeVos, Axios interview, 2017

The other day, whilst tending a towering bonfire in my backyard, I sent my son to the grocery store to pick up some mint leaves and club soda so that I could conjure up some delicious mojitos. He trudged off under the beating sun while I turned my attention back to the flames licking the lower limbs of the highly flammable evergreen trees that demarcate the southern perimeter of my property. About twenty minutes later my phone rang. It was Satchel, sounding wan and sweaty even through the tinny microphone. “I walked over to the high school and the gate was locked,” he said.

There are basically three routes to the grocery store, and for a long while cutting through the high school campus was the best of them, but when Covid arrived the authorities got squirrelly about the notion of members of the unmasked public potentially spreading contagion to the empty building and opted to exercise their consequential power over our freedom of movement. This is not how fascism happens, but it’s plenty worthy of griping. Fortunately, the second route is better.

“Why don’t you take the Beltline?” I replied, referring to the pedestrian walkway which, though not yet paved in our part of the city, has been stripped of the inconvenient railroad tracks which had lain upon it since the days when it was used to supply the neighborhood concrete plant with sand. Whoever took the rails also took away all the heaps of spilled sand which tended to fill the shoes of anyone dumb enough to try to use the right-of-way as a ped xing. It is now the most direct path to mint leaves and club soda.

“How do I get to the Beltline?” he inquired in turn.

“You can literally see it from our front door,” I pointed out after a beat calculated to amuse myself. We discussed street names and the points of the compass and how to shoot the sun with a sextant until I was confident he was equipped to cover the six hundred yards between his position and that of the nearest staircase to the old railway embankment.

Another twenty minutes passed and my phone rang again. It was my wife. “Satchel called to tell me he felt faint and I told him to go home,” she informed me. He couldn’t take the heat, I thought to myself, throwing a broken kitchen chair onto my conflagration. I guess he didn’t want those mojitos badly enough.

These kids today, am I right? Well, Satch can find his way around virtual worlds with aplomb. Like most of the kids in his generation, he finds digital networks more interesting than sweltering asphalt streets, paths and alleys choked with poisonous vines and stinging insects, sketchy people armed with long rambling stories about how they have a job waiting for them in Louisville if they can just get enough money for a bus to their sister’s house in Tallahassee where their wife and kids are waiting to be picked up for the big move, and so forth.

When I was a kid, virtual worlds were still just a twinkle in William Gibson’s eye. Without digital spaces, young folks had to struggle to find a place to simply be. We weren’t exactly welcome to just hang around inside stores, though God knows I tried. Radio Shack clerks knew me well, and I like to think they were impressed by the simple programs I’d write on the TRS-80 computer they’d have out on the counter:

10 PRINT “FLETCH IS GREAT ”

20 GOTO 10Bookstores were great places to while away a few hours, sprawled in the aisles reading entire books and reshelving them in the wrong place. And virtually every department store had an Atari 2600 on display; once at Sears I played Missile Command until tendrils of smoke began to rise from the case and the screen went all schizzy.

This sort of thing generally deprived me of any chance of passing myself off as a potential customer, so my tenure as a creature of air conditioning was always short. Sometimes I lived close to a library, but usually not, so the commanding option was always to to go outside and roam around like an animal. So that’s what we—myself and the packs of feral children I called friends—did.

I’m not saying we were better for it. What, after all, did we derive from this behavior other than copious exercise, lots of vitamin D, and the mental stimulation that comes from telling your own stories using only what the environment naturally provided? Nothing, that’s what.

Ok, granted, it had its benefits. But I don’t think it’s fair to say it was better. Just different. Let me tell you a story:

A couple decades ago I bought a computer. It was one of those white egg-shaped things Apple sold when they were still a hungry bunch of weirdo rebels and not a protuberant market monarch spilling morbid flesh over the edges of a brushed aluminum throne. It came, as computers usually did back then, with a seemingly random collection of software—some typing tutor thing, perhaps a sampling from the Time Magazine archives on CD-ROM, and invariably a game. The game, in this instance, was Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 4.

I’m not at all above playing video games; I have at times been fairly obsessed with certain ones, but this was neither a topic nor a game style that interested me. It’s essentially a sort of rhythm game, requiring you to tap keys in various sequences and at specific moments in order to pull off a litany of skateboard tricks which increase in complexity as you move through the levels. Each level takes place in a different locale. One of these was an intricate reproduction of the San Francisco waterfront. Overall it’s an incredibly stupid way to spend one’s time, slumped for hours in a chair while your blood vessels fill with clots, watching a buff digital avatar shredding tirelessly under eternal sunshine in response to the spasmodic twitching of your fingers.

Like any hard drug, I played initially because it was free, and later because I couldn’t muster the mental fortitude to stop. I played it in the cold dark of the night; I drew the blinds during the day and poured my youth into it; I honed my fake skateboarding skills to a dizzying pitch—if ever at a public gathering some sort of crisis occurs and I hear a cry of “Is there a Tony Hawk Pro Skater 4 expert in the house?!” I will stand up with pride, flex my fingers, and step forward confidently asserting, “Step aside! I am a Tony Hawk Pro Skater 4 expert!” I don’t think this is very likely, but I have to justify all that wasted time somehow, which in fact is a large part of the reason you’re reading this.

Eventually I grew tired of tapping out ollie kickflips and Tony Hawk’s magnum digitum opus lost its shine, receding into a dusty, lonesome corner of my hard drive. A couple years passed when I found myself touching down in the real San Francisco for the first time in my life. I was attending a conference for software developers (real ones, sadly—most of the attendees were rather more corpulent and pasty than maestro Hawk) and had arrived a day early so that I could spend time getting to know the city. It was sunny and beautiful and almost entirely unlike any place else I’d ever been (but with the faintest hint of fraternity with Boston), and I walked until my feet swelled up so large I could hike over to Alcatraz without getting my pants wet.

Late in the afternoon I trekked over to PacBell Park to watch Nomar Garciaparra and the Dodgers play the Giants, with Barry Bonds knocking at the door to Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record. On the way I passed through the Embarcadero, and found myself smacked hard right across the parietal lobe with the realization that I’d been here before. There was no mystery to it—no sense of deja vu or stroke or alien abduction or out of body experience. Just the sudden insistent sense memory of skateboard sounds. Steel trucks grinding along curbs, wooden decks sliding along stair railings. Every side street, every trolley stop, every building was familiar to me from countless hours spent seeking out places to pull off the perfect backside lipslide. The sensation was a lot like when your arm falls asleep and you see it and don’t realize for a moment that it’s your arm, except in this case it was my brain that had fallen asleep and was suddenly the interloper.

“The map is not the territory,” said the philosopher Alfred Korzybski, but what about video game maps? They are certainly models. Is a model a map? Perhaps, but if so, a map not just of the territory but of the experience of moving through the territory. Video games map the physical and the experiential. I don’t think one can argue that this is entirely novel, but video games do it seamlessly. Which is kinda neat.

It was William Gibson’s 1982 novel Neuromancer that ushered the word “cyberspace” into the public consciousness. “Cyber-” was derived from an earlier coinage, 1948’s “cybernetic,” dreamt up by mathematician Norbert Weiner and defined as a “theory or study of communication or control.” “Cyber-” was a hot property for a while, finding itself plugged into all sorts of words (“cybercrime,” “cybernaut,” “cyberpunk,” “cybersex,” etc.). It’s obvious in retrospect that nobody quite understood what exactly was going on but there was a general sense that computers were about to change the world into something that involved a lot of neon, Kanji characters, weird clothes, and crime.

There was more depth in Gibson than all that nonsense, but not everybody reads, so a lot of people were getting all of this second hand, mostly through movies. And man were there a lot of movies—terrible but hilarious failed attempts to bring Gibson’s meticulous world-building to a mass audience using a medium that is by its very nature about appearances. Film is something that defines the border of a soap bubble, and film, in the cinematic sense, can only do interiority via voiceover, which is cheating, or through the facial expressions of the characters, which the best films often exploit for their inherent ambiguities.

1992’s Lawnmower Man has none of that. Featuring Pierce Brosnan in what by all rights should have been a career-ending role as a mad scientist experimenting on Forrest Gump with drugs and virtuality (or what we now call weeknights), the producers of Lawnmower Man apparently didn’t bother with a script or competent direction or acting, opting instead to tell a story through computer graphics which look like they were produced by a 14 year-old who’d learned how to use Video Toaster on his dad’s Commodore Amiga.

So too 1995’s Johnny Mnemonic. This craptacular waste of money, which one critic described merely as Johnny Moronic really did crash the career of the hulking Swedish mannequin Dolph Lungren, for a good fifteen years anyway. Keanu Reeves stars as the title character, a man with a head full of computer chips doing the whole “one last job” thing in exchange for getting the chips out, which underlines the Luddite perspective that belied many filmmaker’s attempts to make the future visually hip. Ice-T is in this movie, which of course stakes it far too firmly in the 90s to allow for any hint of a vision extending beyond the end of the week in which it was completed. It does, however, predict a pandemic striking the world in 2021, but, as though in a nod to the conspiracy theory that Covid-19 is caused by 5G cell phone towers, the film’s illness is caused by a proliferation of electromagnetic radiation.

Most films about computers or virtuality are really about fear of the future. Even movies that are halfway decent, like Tron or WarGames, are just fairy tales in which the protagonist aims to put all of the disruption of the digital age back into Pandora’s box (always successfully, because this is Hollywood we’re talking about). And fairy tales they truly are—the computing that takes place in most films is not anything of the sort. WarGames is practically alone in terms of major films portraying any computer activity without resorting to subterfuge or sheer magic. How many times have you watched a fictional “hacker” lit by the green light of a terminal interface, or more likely many overlapping terminal interfaces filled with rapidly scrolling columns of numbers or arbitrary code listings, eyes darting birdlike as though any human being can actually take in information in this way? How many times have you watched a plot point dissolve under a snare roll of keystrokes administered by a pimple-faced kid who lives on a diet of Doritos and Mountain Dew? This is not science fiction. This is deus ex machina, though the machina is an HP Thinkpad and the deus is pubescent.

Medieval teens attempting to hack into the the Holy Roman Network. Note the hoodie and the eerie blue light.

Even pedestrian depictions of computer technology are marred by an inexplicable sense that people who make films have never interacted directly with, say, a laptop or an iPhone, but only had it described to them. Interfaces are huge and clunky with giant block letters, and often accompanied by annoying beeps and alarms. Computers do things we all know perfectly well they can’t do, and fail to do things that have as much familiarity to us as sock lint. It’s this obtuse and near universal anti-aesthetic that makes us thrill at anything even halfway clever, like the depictions of text messages appearing next to characters’ heads in the Benedict Cumberbatch adaptation of the Sherlock Holmes stories. The creators in that instance trusted that audiences in 2010 had actually seen cell phones and had in some instances even sent text messages of their own, and the result is a device that is aesthetically pleasing, doesn’t require crazy artificial behavior by characters to make the the information clear to the viewer, and as a bonus can be altered and adapted for different dramatic purposes. More of this, please.

None of this would mean a thing were it not for the fact that at some point between the awkward beginnings in the 80s and 90s and today, virtual spaces actually started to appear in the world, mostly but not entirely in the guise of video games, largely unheralded as anything more than that, and completely unrecognizable vis-a-vis what we’d been told by the silver screen. The initial bloom is long gone, relegated to the visual language of those bygone decades—from the glitchy 8-bit Patrick Nagel-esque Max Headroom to the gritty Asiatic Times Square feel of Blade Runner—and the fear has largely dissipated as well, the Matrix series notwithstanding. What’s left is richer, like a stew that’s been allowed to reduce. We have the nostalgia and raw utilitarianism of Minecraft, the hyperreal territories of any one of a dozen different 3D shooters, the stylized universes centered on characters like Mario, the non-rational worlds of deck-building games, dance/music games, and a host of others.

And suddenly, in March of this year, virtuality became very important. Fitfully but inexorably we shifted whole realms of activity into virtual worlds, and we could do this because they were already there, waiting for us. In many ways this seems like a huge blessing. What could Anne Frank do with the long days trapped in a 450 square foot cupboard? How did the 45,000 Union soldiers held captive in Andersonville, Georgia, on a treeless field, devoid of any kind of shelter, clean water, or food beyond a bit of parched corn pass the long weary months? What about the survivors of the Essex, sunk by a sperm whale in 1820. How did they pass the empty days in their empty long boats? We live in hard times, but at least we have Netflix.

We found, when we needed it most, a fully formed virtual universe we can inhabit like Poe’s masquers seeking respite from the spectre of the red death by holing up in their castle. But just like those doomed partiers, we brought all our sins inside with us. And also like them, we wear masks—it’s the nature not just of the time but of the medium; we’re all just assemblages of text and pictures and video clips, lacking the warmth of flesh, the energy of physical presence. We’re not quite human.

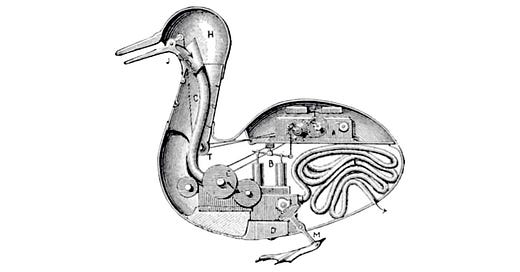

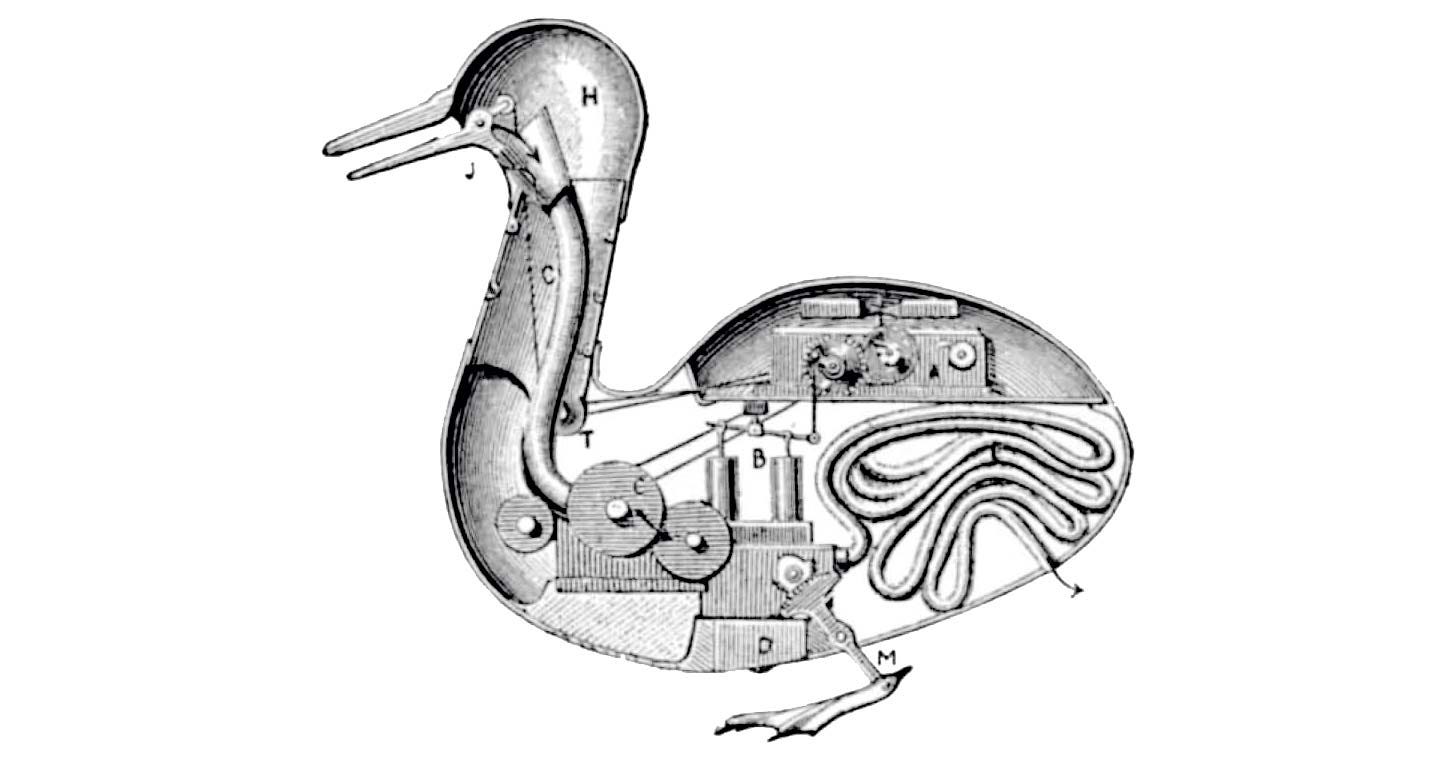

I ran across an interesting quote from the aforementioned Norbert Weiner while researching for this piece. In 1964 he wrote, “The future offers very little hope for those who expect that our new mechanical slaves will offer us a world in which we may rest from thinking. Help us they may, but at the cost of supreme demands upon our honesty and our intelligence” [emphasis mine]. It’s hard to read this now and not think of Twitter, and the pervasive falsehoods visited upon us not just by he who shall not be named, but as well by one another. It’s never even entirely certain, in fact, that an interlocutor in an online forum is really a human being at all, though it must be said that even the bots are acting on human intentions, most of them bad.

It’s a pity really, that we can’t take more from games than just the space. There’s little sense of play or fun in the virtual vehicles we’ve created for politics. They are structured more like a brawl than anything worth exploring. And the same goes for work. Years ago a guy told me that his company arranged a tour of the Georgia Aquarium before the construction teams had even broken ground. They converted the architectural drawings into Unreal Tournament levels and a group of stakeholders participated in the equivalent of an old school LAN party, walking around the virtual space and shooting the walls whenever they wanted to make a point about some detail or other. We could all be out doing slappy grinds on the curbs of San Francisco, but no—our preferred space for online work is essentially the conference room we used to inhabit, except that instead of all of us being in one box, we each have our own. We call them Zoom calls even though they are flat and tedious, or Teams conferences, even though teams play games and the only thing we’re dunking is donuts at home, or Bluejeans, which I guess refers to what we’re wearing while we’re meeting but really just underlines how uncomfortable we still are with the idea that in cyberspace we can wear whatever we want and not just pick from the withered dichotomy of “at work” or “at home.”

I suppose this is pretty small potatoes though, given that for the first time in fifteen years I get to work next to an honest-to-God window. There are both injuries and opportunities aplenty, but really “there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” Hamlet knew he could change his mind yet still thought of Denmark as a prison. Was he really the author of his own thoughts? Are any of us? Maybe, at least in part.

When school started back a couple weeks ago, we joined a pod. Our kids continued the virtual education that began back in March, but they did so at the art studio belonging to Satchel’s best friend’s parents. I was thankful for that, but we quickly realized we’d be unable to keep it up while I was still playing music. My band’s rehearsal space is just short of three hundred square feet, which is decent for four people, but singing in an enclosed space is pretty much the worst thing you can do under the circumstances, and so I received what amounted to an ultimatum—I had to stop or take my kids out of the pod.

I’m not especially vulnerable to the blues, but music is one of the very reasons for my fortitude. I spent a week lamenting this turn of events and steadfastly avoiding telling my bandmates. Finally the day came when I couldn’t avoid the issue any longer, and I sent them a message outlining three options: play acoustic music in someone’s yard, which I knew they would never go for; find a different bass player; or shut the band down until a vaccine or the end of school. I figured there was a good chance this would end the band’s twelve-year run.

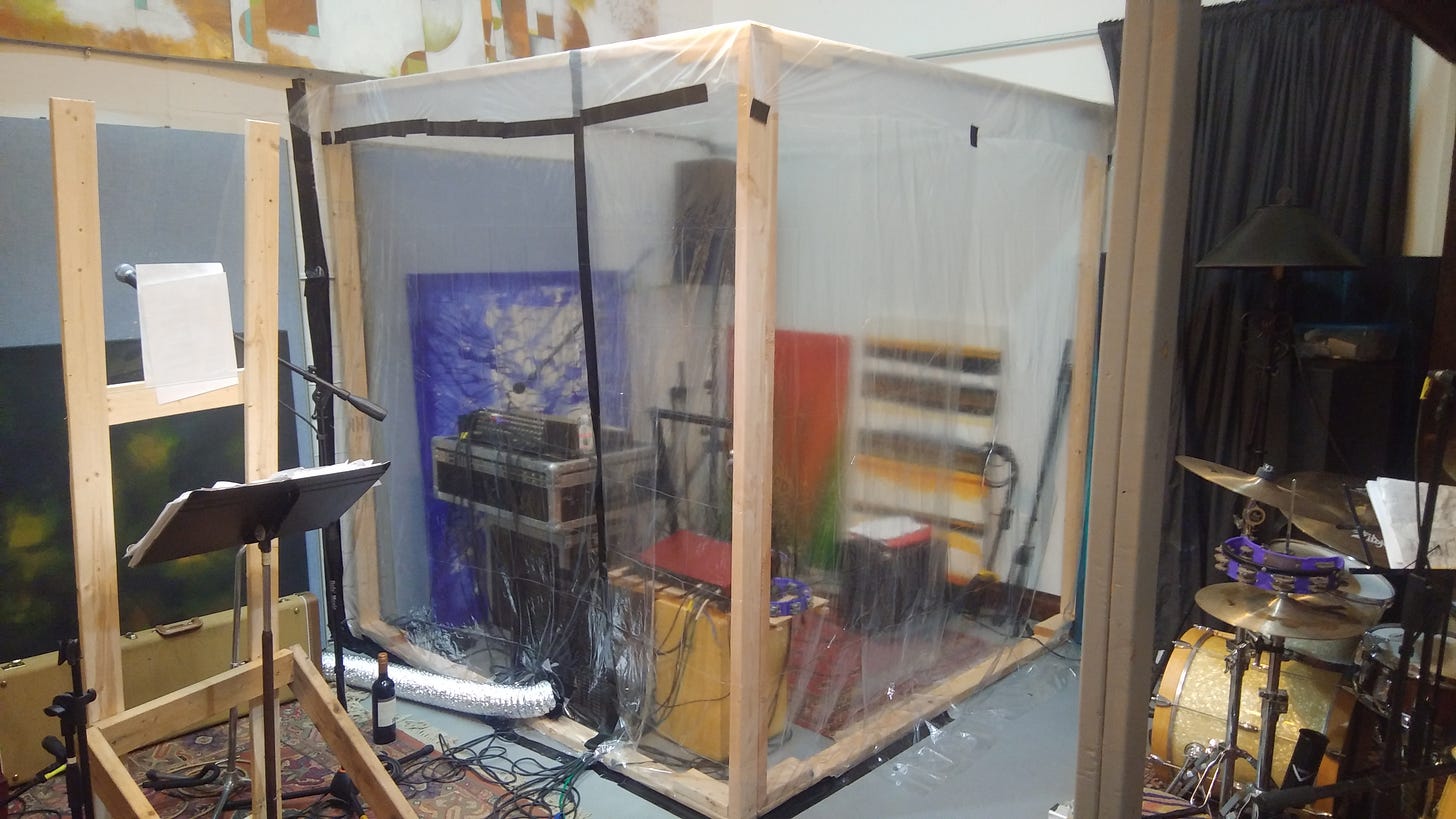

Even as I sent the message, though, a fourth option occurred to me. I could build a new type of space. And that’s what I did. My wife and I constructed a seven-foot square box in one corner of the rehearsal room, covered it in transparent plastic, and ran a ventilation hose along the wall to the window. We placed a fan in front of the junction between the hose and the plastic wall, to draw in air and provide positive pressure inside my bubble. It’s somewhat ridiculous looking, and inside both the temperature and the humidity hover around the mid-80s, which makes it feel as much like a sauna as a practice room. I probably lost five pounds the first time we tried it out.

But hey, music! Apologies to Hamlet, but I count myself a king of infinite space.

Thanks for reading y’all. Thanks to Ken Gordon for his tireless editing of my heaps of words, and apologies for possibly stealing either his joke or his childhood, though we grew up around the same time and both wrote terrible programs in BASIC for 8-bit computers. In any event, if you enjoyed it, you can read it again here.