Discipline

One simple trick to make the bullshit go away for a few minutes.

The fortnights pass by with the regularity of the ticking of a clock, and each time I spot RCB Tuesday1 on the horizon I pause to look back at the fortnight which has just passed. In the six months since a peddler of suspicious cuts of meat2 and eye-stabbing gold tennis shoes took the oath of office as president of these barely united states, each fortnight has looked more or less like the one that just passed—the only variation is that in the faces of the desperate and the malevolent. The rhythm of the seasons is muted, as the weather is reduced to a selection of poisons to be ameliorated with the same purgative: more time indoors, in climate-controlled spaces. Even the 24-hour news cycle seems as though it’s been shattered and reconstructed as a conveyor belt strewn with jagged shards of outrage.

I find myself thinking of a scene in Catch-22 in which our hero, Yossarian, watches a pair of nurses tending to a soldier who is encased in a tomb of bandages covering every inch of his body, frozen in a bug-like pose on his back, arms and legs raised. The nurses nonchalantly remove a bottle from a pipe cemented to the man’s crotch and swap it with a bottle attached to a pipe cemented to the man’s mouth. Rinse, repeat.

The sameness of time now mirrors the sameness of the “content” that now seems to comprise the bulk of our lives, either as consumers or creators or—and this is what I do by way of a day job—facilitators of creators. It seems that no event can change this dynamic—it’s all just further grist for the mill, a mill which is now increasingly automated. Siri, destroy a 250 year old republic.

It’s a hard world in which to be a writer. The story of the last six months is not a good one. It’s not a quick and clever fun heist narrative like Oceans 15 or 19 or 47 or whatever they’re up to; it’s not a tense techno thriller brimming with tough but nerdy guys in big glasses like The Hunt for Red October. It’s not even a funny political satire with Peter Capaldi being hilariously crude and relentlessly Scottish like In the Loop. No, if anything, it’s like a feverish, flatulent Wrestlemania marathon. Just a constant stream of sweaty, visibly black-hatted, interchangeable villains and sweaty, ham-like situational heroes locked in a swirling fight for shifting, fatuous stakes and overdramatic purposes. Too banal for serious engagement; too ugly to look away.

Now it just so happens that there is an answer to this problem, or at least a way of ameliorating it somewhat: discipline.3 If there’s one thing I’ve found over the five years since Covid forced us all to rethink what we do and how, it’s that without a steady daily routine, I am toast. Now, it just happens that my employer is about to stick a knife right in the kidney of my routine, but with any luck that will only be temporary. In the meantime, I figure I’ll do you a potential favor and drop a few words about my routine, why it’s helpful, how I came to it, and how I’m trying to make it better.

Routine is a particularly valuable tool right now. Given the instability of society and government—and the shoe that hasn’t yet fallen economically but which surely will soon as the ripples from Trump’s actions continue to spread outward—having access to something consistent is very important, in part in the interest of not living day to day mired in quicksand, but also because a steady routine is the key to doing anything that can’t be done in a single, desperate, four-hour, coffee-fueled mania.4 If you want to do something great, according to words that recently drifted through my transom, do something small every day.

Now, it took me a good fifty years to really firmly learn this lesson, even though I had put the idea into practice once or twice in limited ways. I did, for instance, ride a bike from the Headwaters of the Mississippi to New Orleans, a journey of over two thousand miles, not in one single 9-day bender, but in 28—or so—70-mile—or so—daily trips. What I didn’t get until more recently was that while daily effort accumulates digestible periods of work into great and possibly staggering feats, it has a way of smoothing out the bumps as well. This is also something I should have learned from biking, where a day with a broken chain and a seven-mile walk down the side of a highway is often offset by 115 miles of flat roads and low traffic the following day.

Today is very much a broken chain and seven-mile highway stroll kind of day. Not today specifically but lately. And in light of the seriousness of our crisis it is indeed hard to justify asking fifteen minutes of your time to read about the strange history of mechanical adding machines or the time I threw up into the washing machine. Not while we have an actual concentration camp in our midst.

But maybe tomorrow?

I understand that some of you would love to read about vomit rather than another diatribe about concentration camps, but to every purpose there is a season, and this is not the season for vomit, other than the kind induced by circumstances. Focused as I am on the long term this doesn’t matter as much to me, the writer. I can keep on writing about vomit in the hope that one day there will be a moment for it. As to readers, there is admittedly value in the distraction that vomit might provide but there is more value in solutions, and in routine is perhaps the only solution I have that doesn’t involve math. So with that in mind let me take a few words to describe what works for me.

I am a lists guy. I have known this for years, but the thing that was always missing was consistency. I would start making lists when the pressure started building up to the point that I began having difficulty keeping track of things. But then I’d get past some deadline or other and the lists would vanish. Now I have a consistent, daily list routine, and I’ve kept it up for well over a year, and it’s made a huge difference for me.

Each morning, when I sit down at my desk, I either make a conscious effort to execute, or accidentally stumble across, my boot-strap list. I really am absent-minded enough that I occasionally forget to do this and wind up frittering away 45 minutes with no discernible direction to my efforts, but the list is taped to the edge of one monitor, situated so that it is at the exact center of my field of view. It usually doesn’t go unnoticed for too terribly long.

The boot-strap list consists of four items: 1) get coffee, 2) take meds, 3) check blood pressure, 4) make daily to-do list.

And yes, without this I would forget to get coffee. Or I’d pour it but leave it in the bathroom or on the kitchen counter. And no I don’t have serious blood-pressure problems; I’ve always trended a little high and a faulty cuff recently gave me a series of false high pressure positive which I’m working to make sure is not actually reflective of reality. But enough about geriatric health care. The highest priority item on my bootstrap list is the last.

I strive to make my daily to-do list before I do any actual work. The items in this list come off one of my big lists, which are long lists I keep in a notebook—one page for work, one page for home projects, and one page for writing. Every single time that a new task appears, even just a glint upon the horizon, it goes into the appropriate big list. Immediately. I know that if I delay so much as 30 seconds there’s a good chance I’ll forget, so this is a hard and fast rule.

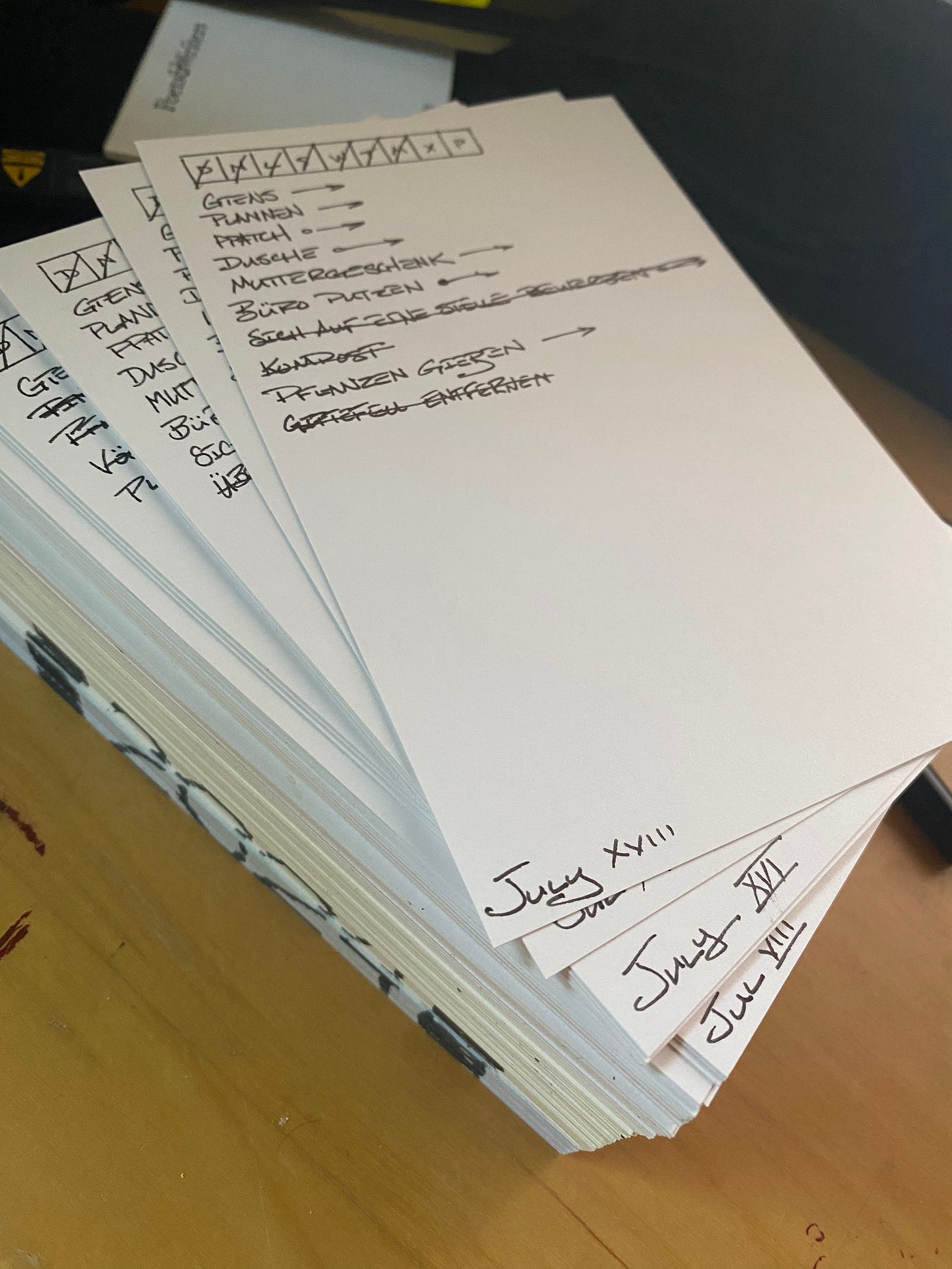

My daily list goes on a five by seven index card. I start by drawing a set of boxes at the top of the card, which I label D, N, L, S, W, T, M, X, P. I write my lists in German because it’s good practice, and these boxes stand for (in translation) German, Dutch, Reading, Writing, Walking, Exercise, Music, Math, and Politics. These are things I aim to do every day. When I finish each item, I check off the box. I’m not an automaton though—I’ve hardly ever do daily math practice, and my political efforts so far are basically garbage.5 But one of the things to know about a daily routine is that there will be problems, and problems require time and creativity to work out. I just haven’t solved these specific ones yet, but that’s ok. It will always be a work in progress.

Below the boxes I list all of the tasks I want to accomplish or at least make headway on that day. As I accomplish items I mark them out. If, at the end of the day, I didn’t finish an item, I draw a small circle next to it with an arrow emerging, pointing right. If I didn’t get to an item at all, I draw the arrow without the circle. The next day I start my list with the unfinished items, and if I’m running short of tasks, I go back to the big list to retrieve something new.

Every list is dated, and I keep them in a stack. That way I can go back and see what I was working on when, or how long it took to finish a given item.

Like all of my routines, this one is very much bound to a location and a set of materials that reside in that location—a place for everything and everything in its place is another motivating idea that plays into my newfound discipline. Ideally this would apply to everything I own but the truth is I have a lot of junk, the place for which really ought to be the garbage. I do, however, have these matters ironed out for the most significant objects in my life. I can always lay my hands on a fresh index card, a pen, my notebook, my meds, my broken blood pressure cuff, my headphones, my glasses, my wallet, my keys, my knife, my phone (and charger), my man purse, my shoes, my hat, a guitar pick, whatever books I’m reading, and an ever increasing panoply of smaller items, because they are only allowed to reside in a few specific locations.

There will always be holes in a routine like this. I still struggle with hitting that kick-start list first thing in the morning. I struggle with a lot of items in my life that don’t belong anywhere specific and tend to drift around. This is particularly difficult with items that need to move around a lot, like tools. I struggle with reviewing my lists in the evening, tending to forget and review the day the following morning, when any insights I might have picked up tend to be muted by the passage of time.

These issues I deal with as best I can. I try to prioritize them, and I try different solutions to each one, generally but not always drawing from the idea of atomic habits—trying, for example, to connect a new habit with an existing one. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t. But again, consistency usually wins out in the end. Continuing to try solutions even as others fail is considerably more effective than griping and throwing things on the floor. So I keep trying.

Starting next month I have to start hauling a portion of my existence four miles to and from my place of employment, as it has been decided by our wise overlords that abject submission to the one-size fits all policies being handed down from the wraparound porch of Foghorn Leghorn is somehow the best thing for everyone. I’ve no doubt this will be devastating to my routine,6 but in typical bureaucratic fashion the quality and efficacy of the work is addressed at best as an afterthought. Adherence to policy counts more than accomplishing ends. No matter. This too shall pass—quickly, if luck is with me. And when the worm turns once again, I will be ready to repair my routine and push it further. It really is the key to getting ahead, and although I wish I’d learned it far earlier in life, I’m happy to know it now.

You’re soaking in it.

The other red meat.

Not this Discipline but I can’t pass the opportunity to hook you up.

As has been my life-long habit.

I bought a box of postcards with illustrations of U.S. national parks to send to political representatives but I find the cards too beautiful to write on or put in the mail. This is my life.

My routine is still devastated by three-day weekends after all.

Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you're gonna get.

Your Mom