I read the news today. Oh boy. A bubbling witches’ brew: eye of newt; child of man; larks’ tongues in aspic; ATACMS and thermobaric munitions. The business end of the world is grinding out some ghastly sausage and all the opinions coursing through internet backbones are no more coherent than any other animalistic shriek of pain, merely sleeker and in some cases generated by LLMs. What we need is a little perspective.

A black screen. One word, blue block letters, “ECHOES.” A ping, as in an old submarine movie—metallic, pointed, bathed in a rippling reverberation.

This is the beginning of Pink Floyd’s 1972 concert film, Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii. The film is based on a brilliant conceit: the band performs an hour-long concert in the ancient amphitheater of Pompeii.1 Pompeii, if you haven’t been following the topic on Muskovision, was flash fried by pyroclastic flow when Mount Vesuvius erupted inconveniently in the autumn of 79 A.D, leaving a remarkably intact ruin populated by the ghastly forms of over a thousand victims preserved in the ash. There have been other concerts in the old amphitheater, but the genius of the Floyd performance is that there is no audience. The place is completely empty but for the band and the crew. Nothing could evoke the ghosts that populate Pompeii more succinctly. Live at Pompeii indeed.

Before I get to talking about how this performance is completely off the Scoville scale, let me explain something to you: I never get tired of Pink Floyd. This is probably the one band on the face of the earth that I’m in the mood for at any time, no matter how recently I last heard them. There’s just something very soothing, almost medicinal to me about their music.

At the same time, I recognize the shortcomings of this band. Spinal Tap taps a different region of rock music, but Pink Floyd is not without their Tappish side. The shots of the quartet galavanting across the slopes of Vesuvius are frankly laughable, and even in their playing there’s this admixture of the ridiculous with the sublime as when the weirdly simian Roger Waters bashes an enormous gong repeatedly at the end of “Saucer Full of Secrets.” Gongs don’t increase the quality of a song in proportion to the number of times you hit them; once is enough, thank you very much. But the scene is intercut with a long shot in which Waters is silhouetted against the setting sun, and lacking individual features is imbued with a certain timelessness, a stab at universality: a human playing a drum.2 What could be more primal than that?

As enamored of them as I have always been and probably always will be, I wouldn’t say Pink Floyd is my favorite band. They’re not the best rock musicians ever to grace the stage; there are plenty of others more imaginative, or with better chops. But I’m not sure there are four people working in the genre who were able to blend together better than Floyd. No one player stands out as the star, and no one instrument upstages the rest. It’s all about the song, or, in their earlier material, the sequence of weird noises masquerading as a song. Correspondingly, their music doesn’t leap out and grab you by the throat either. I’m not entirely sure when I even originally became aware of them; they were just always sort of there, appearing dutifully on rock radio in the early 80s when I was busy being galvanized by the Rolling Stones’ “Start Me Up” and AC/DC’s “For Those About to Rock.” By the time I was in high school I knew Dark Side of the Moon and The Wall as well as any casual fan given the fairly large number of radio singles, but I haven’t the faintest recollection of hearing them for the first time.

Live at Pompeii was another matter—I know precisely where I encountered it. I suppose otherwise Floyd might have remained forever one of those bands you know from the radio but don’t really know. Oh it’s that song. Is that Pink Floyd? I’ll be damned; I always thought it was Electric Light Orchestra. But Live came to me at a key moment and in a key place. Let’s go back, shall we?

My best friend in high school was one of the first people I knew to get a VCR. And being technically clever people, his family in fact bought two—one VHS and one Betamax. If you don’t know, these were basically the Coke and Pepsi of video cassette recorders, which is what we used to watch movies in the olden days before the Internet filled our lives with content and drained them of meaning. Betamax was the superior format but for whatever reason—let’s just chalk it up to human stupidity—VHS won out. Aaron’s parents must have been hedging their bets before the matter had been decided, but even as Betamax underwent its death throes they emerged with a powerful advantage over the typical puny single-VCR family: they could make copies.

And so they did, producing a sub-library of Tower Video’s offerings, a set of films that in my mind form a unit—a canon if you will—and which, by virtue of the ceaseless viewing and reviewing by myself and my small cohort, became one of the substrates of my adult personality. Brazil, Repo Man, The Blues Brothers, An American Werewolf in London, Monty Python’s Holy Grail, A Clockwork Orange—if you ever wondered why I am the way I am, a semi-arbitrarily curated collection of films from the 70s and 80s is part of the answer.

Live at Pompeii was among them.

I was hooked the first time I slid the tape into the thin steel deck, shoved the deck down into the machine amidst a soft tattoo of sliding and clicking mechanical levers and latches, laid my index finger atop the substantial knurled block of black plastic labeled “play,” and pressed. I was hooked from that first ping.

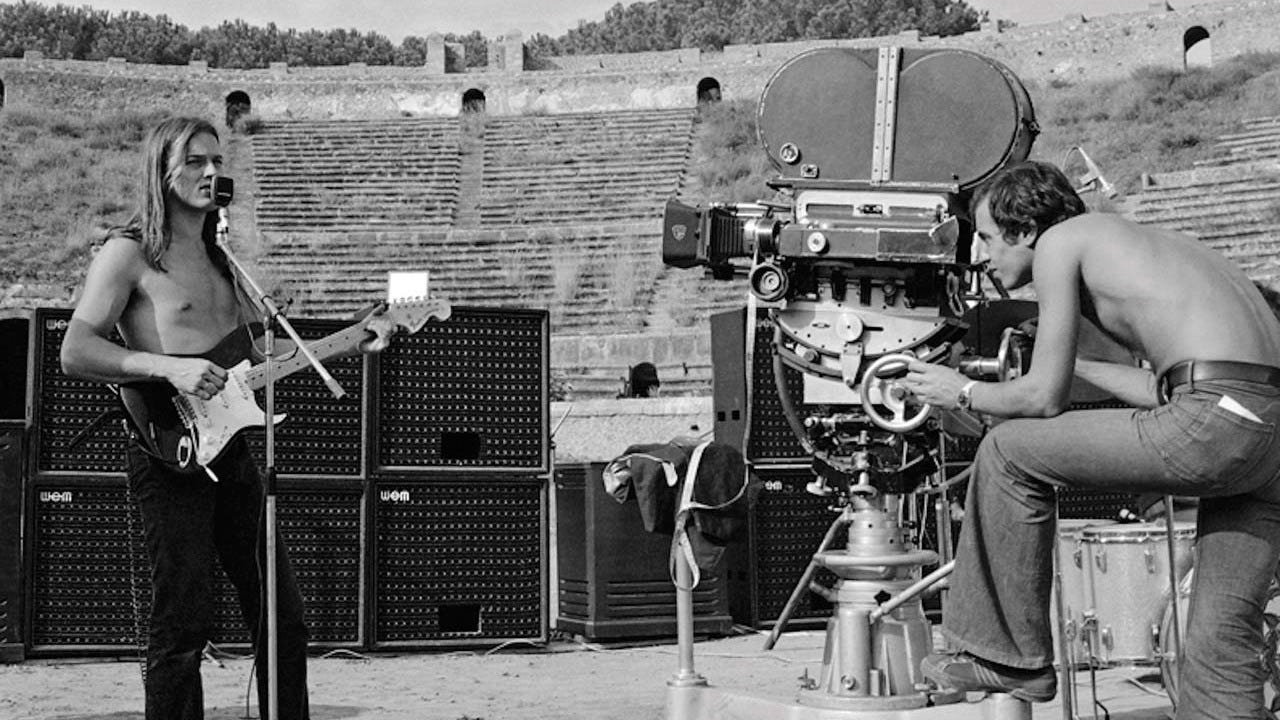

There’s a wistful quality to Live, and a sense of pervading loneliness, which the music complements perfectly. The long, creeping tracking shots, reminiscent almost of Stanley Kubrick—inching along the back of a wall of amplifiers, each stenciled in white, “Pink Floyd, London;” orbiting Nick Mason’s glorious glittering metallic-finish Ludwig drum kit; crawling across the front of the band, Waters in ill-fitting clothes and Wendy Torrence hair, David Gilmore standing shirtless in the dust-filtered light. The lingering shots of the late Richard Wright’s ring-bedecked hands strolling languorously across both keyboards of an enormous Farfisa organ, one of those great chunky and colorful pieces of musical equipment that existed before computers flattened everything and put it all behind a pane of glass like a zoo animal. The number of shots highlighting band members playing whole passages or solos is almost shocking; you can actually see what these four fine craftsmen are doing! I always find the frankness of this approach a welcome purgative against the daredevil camerawork and frenetic editing that characterizes most modern concert videos. And yet, despite the leisurely pacing, the film is never boring. The tracking shots are always revealing some new perspective; the lengthy fixed shots are interesting simply because it’s interesting to watch these four highly sensitive people just work.

And despite the Monkees-esque scenes of the band traipsing around bubbling fields of mud pits with idiot grins on their faces—in one instance Gilmore can be seen rather daintily carrying around what looks like a shopping bag—the scenes of Pompeii and the plains around Vesuvius always serve to ground the enterprise. The point of the concert can seem a little on the nose when the editing cuts from Waters’ elongated and oddly angled face to an equally peculiar visage in stone mosaic from one of Pompeii’s ruined walls, but the ghosts of Pompeii are present in spite of the juxtaposition of their ancient haunt to the almost fetishized images of speaker grilles and Hiwatt logos. They are relentless in their presence.

Sometimes I think that Pink Floyd captured something in their best moments that set them beyond mere rock ‘n’ roll, beyond the iconography of gear and strutting codpiece choreography. The greatest achievement of Live at Pompeii is that the music the band produces is actually suited to the venue. It is as full of ghosts as the air around them, and if it were possible to produce a modern rock soundtrack for a two-thousand year old city, well, for me this is it. I reckon, should my foot ever tread the hoary stones of Pompeii, in my mind’s ear I will surely hear it: clear, metallic, soaked in reverberation. Ping.

Yes, some of them are shot in an empty concert hall in England, but that’s beside the point so just drop it.

Drum in the broadest sense of course. A gong is not a drum. I know that.

Agreed. There's a sweet spot that, for me anyway, runs from Meddle to The Wall. I suppose to some degree that's a personal thing -- every band has a sweet spot for me that might be different for someone else. But that period does include one of the best selling albums of all time, so they got in a little poke at universality.

I listened to Pink Floyd's entire output (although I haven't seen this movie) for the first time last year. My verdict, the albums that are famously good are as good as they are famous. The other albums are actually pretty bad. Not that different from most bands, except in the degree. Your assessment of their strengths is quite astute.