“To look at the paper is to raise a seashell to one's ear and to be overwhelmed by the roar of humanity.”

― Alain de Botton, The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work

In a fit of optimism I recently paid for a six-month subscription to a large online archive of newspapers, like I was gonna read em all, and occasionally I remember this purchase and go trolling, feeling a lot like a kid meandering along the strand in search of a whole conch or at least a clam the size of your hand and lined with perfect mother of pearl. It always begins as an engaging activity, and I enthusiastically clip pieces with the notion that I’m engaged in some meaningful research task, but the exercise always grows gloomy and eventually exhausting, as I start to realize how far the beach runs and how many tiny fragments of stories make up the sand, and how lightly my own story, like Canute standing athwart the tide, impedes the flow.

The biggest thrills come from recognizing family in this vast yet vastly insufficient chronicle of the past. It’s like spotting a friend in an unlikely place, like standing in line to buy fried crickets at a Japanese baseball game or carrying two bags of groceries down the center of Bourbon Street in New Orleans on the Fourth of July.1 I received just such a little burst of frisson while idly searching for one Loretta McDonald.

My little family, shredded by three years of nonstop death and divorce, arrived in Nashville right in the middle of the eighth grade. It was me, my mom, my sister, and my grandma Loretta, who did most of the grocery shopping and cooking. Winn Dixie had this Bingo game promotion going at the time, where you had a Bingo card at home and every time you went to the store they’d give you a bunch of stamps marked with the standard Bingo row/column index, e.g. B1, D5, and so forth. If you got a Bingo there was a foil scratch-off box that concealed the prize, usually $10 or some choice of free products.

Just as the school year ended, my grandma won a hundred bucks. She gave me $10 because I was the designated Bingo administrator, managing the couple dozen cards she had. She made a big deal out of it and it was a lot of fun and adjusted for inflation that was like $260, so probably pretty meaningful. We weren’t starving, but we were pretty strapped, what with that sumbitch Reagan in the White House.2

Anyway, I looked her up: Loretta McDonald, Nashville, 1983 until her death in ‘98. A Winn Dixie circular came up, advertising Bingo winners in the $1000 and $100 amounts, and there she is at the bottom of the list, “Loretta McDonald, Nashville,” a faint star still gracing the firmament forty years later.

I had the New York Times delivered to my dorm every day during my (second)3 freshman year in college. This was a ridiculous arrangement and the Times’ subscription office should have turned me down on the grounds that the resulting surfeit of newsprint was causing the Earth to wobble on its axis. It was not enough to just crack the paper open every now and then and read a piece about cooking with mineral oil—I looked at the news like it was a novel, and if I hadn’t read about what Yasser Arafat had done yesterday there was no way I was going to understand what Yasser Arafat was doing today. So I would literally sit down every couple of weeks with a determination to “catch up,” reading one paper after another until I reached the present.

Or, more often I just let them pile up even higher.

At some point this became a convenient way to keep my roommate’s pet duck from shitting on the floor, but it was still too much. At some point it became apparent that if I didn’t do something I’d have to start sleeping out on the quad, so I cancelled my subscription and never received regular delivery of a physical paper again. But I haven’t given up on the idea of papers as narrative, and even as I write this I have probably fifty tabs open with stories I’ll probably never read.

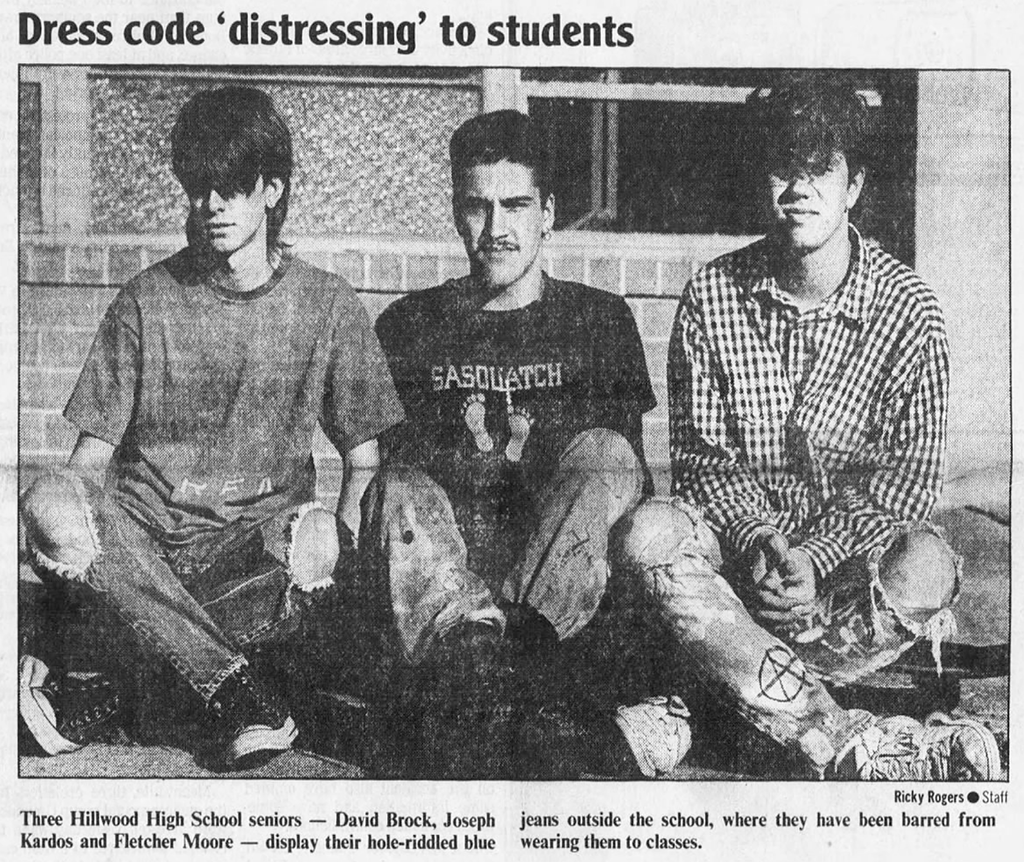

If I don’t do something now, before I shuffle off this mortal coil, I will be remembered to posterity as a painfully unselfaware teenager in a blue-checked shirt and bluejeans speckled with bleach spots and shredded at the knee, on the front page of the April 26, 1987 edition of The Tennessean. My hair obscures my eyes but the carefully inked circle-A on my pants leg is eminently visible and saying oh so many embarrassing things about me but not so much about anarchy as a political philosophy. The article is titled “Holey jeans, a hot fashion, cold reception at Hillwood.”

I don’t remember how this became a newsworthy subject, or how I wound up at its epicenter, though I do remember that the day after my high school banned holey jeans I performed an act of staggering sacrifice and selflessness, throwing my flesh, clad in freshly holed jeans, directly into the gears of the educational-industrial complex.

I was suspended for two days. This was the pinnacle of my life as an activist.

The article quotes myself and my fellow students, and honestly, on a subject this stupid, it’s very hard to sound like anything but an effete asshole when you’re bitching about not being allowed to wear flipflops to the office, but I still managed to sound like the dumbest guy in high school, telling the reporter that in my chosen field, which that day was music, “success … consists in wearing whatever you want. I don’t think a suit and tie is exactly going to do.”

Ok, sure. The writer picked out the most juvenile remark in a five minute conversation otherwise dancing with first-class witticisms, but there’s no avoiding the fact that these words, or something like them, escaped my lips. David Bowie, hello? The goddamn Beatles?

It could be worse. I could have been one of the 15 indicted congressmen in the neighboring article, or I could simply have been the Hillwood principal, whose words will remain accessible possibly for thousands of years to come, saying “the holes in the jeans tend to move up into the crotch area.” The puritanical fear coming off the man is palpable; one can easily imagine him carefully measuring the distance between amorous prom dancers with a ruler.

I still have time to live that down, but not everyone is that lucky. I figured as long as I had every newspaper in America at my fingertips, I may as well take a look and see if I could glean any interesting details about the lives of various aunts and uncles at some remove from me. Most defy a quick search or turn up, at best, a brief and enigmatic obituary. But not Francis Conyers. Francis was one of two younger brothers to my grandma Loretta—the mid-kid in a family with an oversize stock of wild stories. I never knew him, as he died in what has been represented to me as a gas explosion in 1963. I don’t think I appreciated as a kid that my grandmother didn’t want to dwell on the particulars of his death: to me he was always just a somewhat mysterious name and a few photographs; she grew up with him. So imagine my surprise when I followed his name to the March 30 edition of the Arizona Daily Star to find a lurid photo of a man struggling to escape a prodigious jumble of flaming rubble beneath the headline, “6 Tucsonians Die, 32 Injured in Cleaning Plant Explosion.”

The explosion at Supreme Cleaners was then considered to be “one of the worst disasters in Tucson’s history,” and the man being assisted from the scene was Bernard Oliver, a press operator who happened to be standing back to back with my uncle at the moment an electric spark ignited an accumulation of gas from a leaky main. Francis was flung completely out of the plant by the force of the explosion; Oliver was by chance snarled on a piece of metal and avoided the same fate.

So Bernard Oliver is like this strange shadow or spiritual doppelgänger of my unknown uncle—the last person to see him alive but also a testament to how things might have been different. One doesn’t wish for the death of others, but it’s impossible not to see Frances and Bernard, who died at age 89 in 2009, as two sides of the same coin. As if to underscore the weird vagaries of fate, a neighboring article tells the story of four women in Kankakee, Illinois, who each drew a perfect hand—13 cards of the same suit—in a game of bridge, a feat with a probability of 1 in 158,753,389,900.

So there in three pieces—or two pieces and an ad if you’re being nitpicky—flashes of the lives of three members of my family. But they don’t say much. One won a hundred bucks, one was a callow teenager, one died in newsworthy fashion. It’s sobering to look at a newspaper—any single edition of any single paper—and catch these little glimpses of people, boiled down to one incident, drops of rain in a deluge.

I read the news compulsively. I tell myself I like to know what’s happening in the world, but my experience of digging through old papers is not necessarily enlightening. Of course I’m dipping more or less at random, but it seems more the exception than the rule that newspapers establish coherent narratives over time. They’re just looking for readers, and so publish whatever catches the eye. What other explanation can you find for stories like the one published in the Atlanta Journal Constitution, entitled “Horseback Trek Well Worth It,” on the very day in August of 1945 that the Japanese gave up their dreams of empire.

The piece tells of a woman who rode with her daughter a thousand miles on horseback to meet her new granddaughter in Seattle. “The horses were butterballs when we started,” she tells the reporter, who continues, “Moseying along at 15 to 38 miles a day, they were soaking wet from rain on occasions and blistered in temperatures of up to 116 degrees. Worst of the trip was when they attempted a shortcut through Tiller pass, over the Devil’s Knob, between Medford and Canyonville, Ore. They went three days without meals and kept to the highways after that.”

It’s actually an amazing story, worthy of a film, but here it’s maybe four column inches, boxed off from everything around it—and mind, everything around it is about celebrations of the end of the war—and without any followup, ever. Of course, in this modern digital world, we can shovel up additional pieces in the Santa Cruz press about the trip, but there’s something simultaneously delightful and morose in the thought that some editor at the AJC on V-E Day thought that this little fragment of a life in distant California was worthy of a place in the daily record.

I’m inclined to turn Joseph Stalin’s formulation—that the death of one person is a tragedy while the death of one million is a statistic—on its head, and say that every person is an amazing tale comprised of millions of stories, and that the sense of vertigo one gets from contemplating the endless depths of space can be apprehended just as easily by thinking about all the billions of lives lived over a couple hundred thousand years of human culture. It can make a person feel very small, but it can be comforting as well, to know that whatever dumb things you do tomorrow or did yesterday, well for most of us the stakes are pretty small in terms of historic impact. You can certainly hurt those around you (and please, people, don’t do that), but it takes real world-class talent to ensure that your name is still being bandied about eighty years hence as a euphemism for toady. Right now that dishonor belongs to Vidkun Quisling; I like to think that when I am gone and my children are old and grey, the worst insult in the political world will be to call someone a Graham.

For the rest of us, let’s all hope to draw a royal flush before it’s all over. Stranger things have happened.

Which one is a true story? Pick one and tell me why you think it’s true. Best response wins a sticker made by my daughter.

Apologies to Joel and Ethan Coen.

This is a story unto itself and one day I’ll tell you all about it.