I spent a chunk of this morning reading Timothy Ryback in the Atlantic, and you should too. Ryback is a superb writer and draws from a seemingly bottomless well of meticulously indexed history, such that he is able to lay his hands on a historical parallel for practically every detail of our current—or, one suspects, any—crisis. He draws most of his material from the collapse of the Weimar Republic, and despite my long fascination with that lamentable history, he never fails to surprise. He presents his material without even a passing reference to modern events and figures, but you can see them as clearly as a neon sign. Consider the following:

[Alfred] Hugenberg had … founded the Telegraph Union, a conglomerate of 1,400 associated newspapers intended to provide a conservative bulwark against the liberal, pro-democracy press. Hugenberg also bought controlling shares in the country’s largest movie studio, enabling him to have film and the press work together to advance his right-wing, antidemocratic agenda. A reporter for Vossische Zeitung, a leading centrist daily newspaper, observed that Hugenberg was “the great disseminator of National Socialist ideas to an entire nation through newspapers, books, magazines and films.”

To this end, Hugenberg practiced what he called Katastrophenpolitik, “the politics of catastrophe,” by which he sought to polarize public opinion and the political parties with incendiary news stories, some of them Fabrikationen—entirely fabricated articles intended to cause confusion and outrage. [emphasis mine] According to one such story, the government was enslaving German teenagers and selling them to its allies in order to service its war debt. Hugenberg calculated that by hollowing out the political center, political consensus would become impossible and the democratic system would collapse.

The flickers of recognition shift and morph like figures in an AI generated video, but they are unmistakable. I believe that Ryback is telling us what I suggested we could learn from Kafka in my last post: Nothing changes but the weather. Watching the wealthy and powerful scrabble heedlessly over one another in their insatiable thirst for more is sickening but also depressingly predictable.

Read the whole thing (paywalled) if you can. I’ll let Professor Ryback do (some of) my bitching this week. You’ve all seen the news, or you are deeply invested in not seeing it. The world will little note nor long remember what blathering I spew here upon this website, so rather than using my precious time to keep prodding you about what you already know, I’ll try to give you something of lasting value.

Before I leave this topic, though, I would like to point out one thing: the future is unknown. The Orange Menace and his little sieg heiling monkey are gleefully demolishing our system, but they are incapable of building anything of worth. This is horrible, but there will come a day when it will have to be rebuilt—hopefully sooner rather than later, but it’s inevitable. When that day comes, there will be one of those rare historical opportunities to improve upon what came before. It was a long haul for Germany, but what they built in the wake of the Second World War was in fact the first successful German republic,1 and for all of its looming instability the willingness of Germans to come to grips with their past—Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coping with the past)2 —has been a really admirable thing, and any nation that finds value in any true virtue has something solid to build upon. There are a great many people in this country who fervently value liberty and justice and rule of law. We need to hold onto that; it will be handy later.

Give your extra money to legal funds—I’d suggest the ACLU but there are plenty of others. And as Mr. Rogers told many of us when we were pups, look for the helpers. They’re out there, and if you can’t spot them, be one.

Now it may seem like I’m unable to divorce myself from the present because I want to introduce my next topic by saying it was evoked upon learning that our new national policy seems to be aiming us toward a conflict with the Danes over possession of Greenland. The absurdity of this move is self-evident, but to me it carries an extra soupçon of inanity because when I hear the word Greenland two things come to mind. The first you probably know well.

Wallace Shawn, ladies and gentlemen. An American treasure.

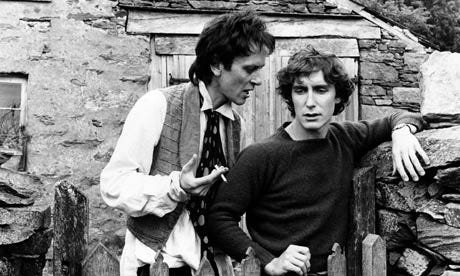

The second involves the incomparable Richard E. Grant; gaunt, wild-eyed, terminally dejected, stalking around a filthy apartment and smearing his skin with menthol cream as he declaims in a stentorian voice:

How can it be so cold in here? It's like Greenland in here. We've got to get some booze. It's the only solution to this intense cold. Something's got to be done. We can't go on like this. I'm a trained actor reduced to the status of a bum. I mean look at us! Nothing that reasonable members of society demand as their rights! No fridges, no televisions, no phones. Much more of this and I'm going to apply for meals on wheels.

This is one of my favorite scenes from one of my favorite movies, the 1987 black comedy Withnail and I. The film tells the story of a pair out of work actors in London in 1969—the titular Withnail, a desperate alcoholic clinging to the last vestiges of a career that is clearly dead in the water and sinking fast, and I, the unnamed (the script refers to him as Marlow and so shall I) narrator and protagonist, played by Paul McGann, who is only slightly less pathetic than his perpetually fulminating housemate. Their situation is desperate and ridiculous as they are both unequipped to handle so much as a shortage of liquor, much less the possible presence of a hostile animal in the murky depths of their squalid, trash-filled kitchen sink. In a vain attempt to jog themselves out of their torpor they persuade Withnail’s uncle Monty, a flamboyant Richard Griffiths given to long homoerotic tales from his own now distant theatrical youth, to allow them the use of his country cottage for a weekend getaway. On arriving, their self-destructive patterns continue unabated, except that they are now accompanied with an entirely new array of problems—food, heat, strange country people, and ceaseless rain. To make matters worse, the following day Monty shows up and begins to make advances on Marlow.

Withnail and I is great both because it’s painfully funny, but also because it’s painful. Withnail feeds off his own self-pity, loudly, in a wickedly hilarious vernacular that sounds like Shakespeare filtered through subway bathroom graffiti, but he is fundamentally a tragic character. He’s completely adrift with nothing but his wit to sustain him, and it’s a wit that makes the viewer laugh even as it’s totally clear that it’s a mask which barely covers his helplessness. His trajectory is fixed, and we feel it even as we titter when he tells a farmer, “We’ve gone on holiday by mistake.” This is not to say that a movie or a book can only be good if it’s multifaceted, but there’s a reason comedies often taper off if they’re too long. Lacking true, meaningful human stakes, two hours of slapstick is like eating a whole box of Oreos.

The original script for Withnail and I had Withnail committing suicide at the end by shooting himself in the mouth. Some bright spark decided this was too dark, and the film concludes instead with Withnail, alone in the rain watching Marlow board a train for Manchester, where he’s been offered the lead in a play. Marlow is moving forward and Withnail’s story, we understand, is finished. Alone, drunk as always, Withnail walks back through the zoo, where he stops to perform Hamlet’s famous soliloquy in front of the wolf enclosure, which I shall quote in its entirety for no other reason than that when I see it in print I hear Withnail’s voice:

I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth and indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame the earth seems to me a sterile promontory; this most excellent canopy the air, look you, this mighty o'rehanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire; why, it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, how like an angel in apprehension, how like a God! The beauty of the world, paragon of animals; and yet to me, what is this quintessence of dust. Man delights not me, no, nor women neither, nor women neither.

You can see it too, but if you haven’t seen the movie yet, maybe you should watch that first.

It is apparent, watching Withnail before he turns to walk home, that he really is a talented actor, and there’s a good reason for his anger at his circumstance, though it is equally clear from all that has come to pass at this point that his chief impediment is in fact himself. And it’s clear too that a suicide would have been an insult to the intelligence of the viewer. We know in our bones that Withnail has no future. We don’t need to be told.

It’s rare to find a film that has the capacity to draw tears of equal measure from humor as sadness, and the bittersweet combination is so utterly human, it’s almost hard to take. But Withnail and I is just so good, from the very first word to the very last, that I’ll take it a hundred times and never tire of it.

This was Richard Grant’s first film, and although he almost always serves in supporting or ensemble roles, I’m always delighted by his presence in a film—even when he isn’t given enough lines to quite steal a scene it’s like spotting a shooting star. Writer and director Bruce Robinson, who is probably better known for writing The Killing Fields, wrote Withnail and I partially as autobiography, and as such it contains oblique references to an occasion early in his acting career when he was sexually abused by Franco Zefferelli when the latter chose Robinson to play Benvolio in his famous adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. Withnail and I is a strange standout for the late 80s—many who watch it assume it was shot in the 60s and not just set there. There’s something so entirely lived-in about the world it creates, from the complete disarray of Withnail and Marlow’s apartment to Monty’s absurdly decorated house, there’s no set that looks built, and none of it looks like either 1987 or 1987’s idea of 1969. It’s as though Robinson simply opened a window on a world that very much existed at one time.

I would be remiss if I ended without mentioning the Withnail drinking game, in which viewers (the film is not particularly well-known in the U.S. but it’s an enormous cult classic in England) attempt to match Withnail drink for drink. Don’t really play it; you’ll die:

9 and one half glasses of red wine

one-half imperial pint of cider

2 and one half measures of gin

6 glasses of sherry

thirteen drams of Scotch whisky

once-half pint of ale

one shot of lighter fluid

Sounds like a baller of an evening, am I right? Seriously, don’t do this. I’m not even sure what a dram is but 13 is too many. At least leave out the lighter fluid.

If you have an HBO Max subscription you can drop everything you’re doing and go watch this right now, but if not you need to get thyself to the library or whatever vestigal video rental store still remains in your area—and you can go very large with the definition of area because it’s worth it—and pick up a copy. You can thank me later.

In spite of the great age of the German language and peoples, the German nation is a relative baby in Europe, having only first coalesced in the year 1871.

And yes, this is a classic German “tapeworm word” (Bandwurmwörter).

Thanks for the reminder. I need to watch this classic again asap.

I just rewatched this recently. Richard E. Grant is beyond brilliant. Withnail is permanently imbedded in my brain. 🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

(Did not attempt the fatal drinking game.)