Dearest Reader: For four weeks, or two fortnights for those of you who don’t know what a “week” is,1 I’ve diligently researched the history of pandemics in search of some insight into what has happened over the last year plus. The result is that I know a ridiculous number of disconnected things about pandemics. In the process of learning, however, I have managed to lose sight of what it was I actually wanted to say, so for the second straight time I’m shelving the subject for later. In the mean time, I have dipped into my shockingly sizable archives (what on earth did I write all this stuff for?) to bring you the first installment of a piece I wrote in the distant past—the year 2015—on the subject of coal-fired power plants in Georgia.

I know what you’re thinking: shut up and take my money.

Ok, I know what you’re really thinking: who cares? Fine. But like most of the subjects that come through my transom, coal was just a flimsy excuse to travel. Coal took me all over the state, in an extended road trip the likes of which I’ve never visited upon any other state with the possible exception of Tennessee, which I have explored pretty extensively on the basis of youth and a youthful habit of pointing the car in a direction and just going, often sans map. But we’ll talk about that another time.

So without further ado, I bring you the first of several installments from Sixteen Tons. I’ll bring you the rest as suits my schedule, so buckle up; it will be a while before we’re done. I hope you enjoy the ride.

The Child is the Father of the Man

When I was a boy, I lived in fear of sudden incineration. This wasn’t an idle fear, fueled by grocery store tabloid tales of spontaneous combustion. What I feared was nuclear war. I was a precocious kid, insofar as a largish chunk of my time was spent poring over books detailing the horrors of World War Two, with which I’ve been fascinated as long as I can remember. I knew in exacting detail what happened at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Somewhere I’d seen one of those charts with the concentric circles overlaid against the map of some hapless city, each circle designating a differing degree of death and destruction; Dante come to life. Everywhere I went I mentally placed these charts against whatever seemed a likely nearby target in order to determine my own personal danger level, like a Geiger counter in my imagination.

In the summer of 1980, after my parents’ divorce, my sister and I moved to rural Michigan to live with my grandparents. There was a lot of bellicosity in the air at the time, what with Iran’s Islamic Revolution the previous year, as well as the subsequent hostage crisis, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December. At ten, this was all pretty vague to me, but I could feel the tension, and it stoked my fears.

We did our shopping in Clare, eight miles from home. Clare is known as the Gateway to the North, which is funny, because things as large as “the North” don’t usually have such comically small gateways. Unless the Soviets had it in for Amish farmers, Clare wouldn’t have been a target, but I didn’t know that. I placed my mental destruction chart accordingly. The city had a tornado siren they tested at noon once a month, unbeknownst to me. So when I first heard the grinding wail rise up into the sky like a great and terrifying sonic wraith, I broke out in a cold sweat and the hairs on my neck prickled. My only thought was, “this is it.” I waited for the flash and the heat.

It never came. And now, thirty-plus years on, the Soviets have gone the way of the Ottomans and the dodo bird. I have kids of my own now. In the world that has emerged to them, nuclear holocaust is just another lesser fear in a pantheon led by a real juggernaut—climate change. This doesn’t represent an improvement. The problems set before their generation are every bit as implacable and irrational as mutual assured destruction, but they are also slower; quieter; less immediately visible; and much more complex, subsuming all of the human vexations that characterized all our previous crises as well as a host of technological puzzles the likes of which the world has never seen.

It’s hard to find hope, and it’s very easy to succumb to a sort of intellectual paralyzation. I can’t imagine what it must be like to be a kid growing up today.

A couple of months ago, while I was busy pickling these fears in a delightful IPA, a friend suggested I write about Georgia’s coal-fired power plants. My jolly mouth said this sounded like a great idea. Later, in the cold light of day, I remembered that I don’t really know anything about coal beyond 1) it’s filthy, 2) it burns pretty easily, and 3) Loretta Lynn. I got to looking at a map, though, and those plants, spread like a bandolier across the broad body of Georgia, slowly began to look like an opportunity. The stories of those plants, after all, is entwined with the stories of the communities that host them. And those communities are chapters in the story of the state as a whole.

I’m not a Georgia native, but at nine years I’ve lived here longer than I’ve ever lived in any other single place (I was an Army brat growing up). My son was born here: my daughter has lived here for virtually her entire life; the first and only house my wife and I have ever owned is here. Georgia is home. And I decided I’d like to know what’s happening in my home.

So over two months, I’ve taken to the road to see those plants up close. To see what they are doing and to whom they are doing it. And to learn too what treasures Georgia offers and how they are bound to the Faustian bargain we’ve all made, consciously or unconsciously, in the interest of keeping our houses lit at night, our computers churning through bits and bytes, our dishwashers washing, our toasters toasting, and our electric razors razoring. I hope that every Georgian has an opportunity to get out one day and see the state the way I have. It’s the best way to see what’s at stake.

It’s also a good way to begin to get a grip on what needs to be done. Today Georgia is pretty much the New York Yankees of coal pollution. We possess the top CO2 producer in the world! Go Georgia! But it’s not all bad. Georgia also sports the fastest growing solar industry in the U.S. In many ways the state can be seen as ground zero on one of those charts with the concentric circles. But what those circles represent— ruin or revitalization—is up to us.

All of us, Georgians.

Roman Holiday23

I drove up to Rome with my family on a Sunday afternoon at the tail end of August to watch the Rome Braves—the Atlanta Braves’ imaginatively named single-A affiliate—take on the Charleston Riverdogs. It was everything a baseball game should be: fourteen innings of shutdown pitching and keen defense on a warm and sunny day. Unfortunately, State Mutual Stadium, while not without its joys, is a reminder of everything that’s wrong with Rome. The facility was paid for entirely through a SPLOST tax, with State Mutual Bank swooping in at the tail end of the process to purchase the naming rights. Indeed, naming rights to pretty much everything in the ballpark, short of the toilets, has been sold to someone; the most hilarious example is the outfield berm apparently called “Appleby’s Home Run Hill.”

Rome proper failed to reveal itself to me on this particular trip. I’ve passed through downtown since then, and although it is certainly vibrant and attractive, it’s buried like a pearl in a dumpster. We looked for it but found only anytown-style plazas full of chain stores. That sounds like an awful thing to say about a place which is doubtless the pride of its 35,000 residents, so I’ll just go ahead and apologize. I’m out of line. Rome has a fascinating story: Some 180 years ago, a small group of military men drew the name of the city out of a hat! Who does things like that? According to legend, the author of the winning entry had been inspired by the river and the seven hills they had chosen upon which to found their city, on the grounds that it was a tiny American simulacrum of the original over in Europe. I don’t know whether this is true — it was hard to see any hills; just Autozones and Subway restaurants and a host of grim little check-cashing blockhouses.

What Rome does have is Berry College, which all alone is as fetching an expanse of land as any city has a right to possess. Berry is like something out of Harry Potter—27,000 acres of emerald green campus at the center of which stands a cluster of magical stone buildings that make Oxford and Cambridge look like seedy trailer parks. Berry is magnificent. It’s beauty warps space and time and probably causes more than a few car accidents among unsuspecting travelers who happen randomly upon it while rooting like pigs for a Chick-fil-A. Rome could have been like Berry, and no, I’m not kidding. The buildings probably weren’t cheap (unless they are inflatable — I never got close enough to be sure), but the land is what it is, at least until you choose to drop a White Castle on it.

Or, a coal-fired power plant.

Hammond Plant is a fair distance outside of town, toward Alabama, where the sheer intensity of sprawl is less marked, though what patches might be found tend to be more mute and sad than merely soulless. What is striking about the plant, particularly in contradistinction to the mean existence being scratched out within its penumbra, is how neat and orderly it appears. There’s no mistaking its industrial character, but it’s surprisingly placid. There’s no movement; nothing seems out of place — even the heap of coal that feeds the hungry furnaces is a trim cuboid, with no scattered inky crumbs or smeared tire tracks within its substantial demesne. The low security building in front of the gate looks like an Eisenhower-era post office; priggish and architecturally bankrupt, but immaculate and taut, like a Marine recruit. The main facility is tall and muscular, a concrete box clothed with a network of pipes and scaffolds, all pregnant with purpose and mystery, all regimented, inscrutably ordered, and culminating in a towering dun chimney which rises into the blue sky like a great bolshy phallus, from the apex of which trails a thin streamer of smoke. A low hum issues from nowhere in particular.

If you didn’t know any better, you might assume there was nothing amiss.

You’d be wrong. It was much later in my tour that I would see plants actively cranking out power, but even then most of what you can see pouring from the stack is just water vapor. The plant could just as easily be a lurching Gilliam-esque deformity thickly caked with dross and crawling with head-cracking security guards—it wouldn’t change the fact that the real damage is invisible. You can’t see the carbon dioxide it pukes into the sky, turning the atmosphere into a seething bedlam. You can’t see the sulfur dioxide that rains on the neighbors, eating away not just their cars but their lungs. You can’t see the mercury that settles in the ponds and rivers, but you can damn well consume it. Eat enough of it and you’ll wither away in the confines of some overtaxed hospital, just as invisible.

Again I apologize. It’s not fair to make Rome the butt of my admittedly childish humor. What has happened in Rome is happening all over Georgia, and indeed all over the United States. We are all offered the same horrible bargain. You can have a prefab community stamped out of fast food and flimsy auto parts, fed by whatever industrial leviathan needs a lair in which to coil up and exhale its poison fumes; or you can have poverty and decay. You get to choose, but in the end, inevitably, you get both.

Harllee Branch: A Capitol Crime4

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Let’s get square about a few things up front. I’m aware that you can’t put sunshine in your gas tank. I know you can’t put your groceries in a bag of sunshine. I understand that there’s a massive sunk cost in our present energy infrastructure. I know, in fact, that coal-fired plants in Georgia provide north of 11 megawatts of electricity, and that it would take nearly two dozen world-class solar plants to match that, putting aside fossil fuels for things like plastic and fertilizer. And yet, none of this is an argument for doing nothing. We had a whale oil economy once too, you know.

Of course, Georgia doesn’t make it easy. In many states you can get a company to install solar panels on your roof and then purchase your monthly electricity from them the same as you do from Georgia Power. In many cases the monthly cost is less than power purchased from fossil fuel plants, and the arrangement spares you the large capital cost of installing the panels. We could do this in Georgia too if it weren’t for the Territorial Electric Service Act of 1973, which basically says you have another one of those funny choices: in most cases, you can buy from Georgia Power or you can buy from Georgia Power. Why does such an absurd, anti-competitive law continue to exist? I’m sure the army of lobbyists employed by the Southern Company has nothing to do with it.

The upshot is that most of us, Georgians, are entirely dependent on Georgia Power to sweep us boldly into the 21st century, should they develop a whim to do so. In a state where free-market principles are second only to the words of Jesus Christ Almighty, we are not free to “vote with our wallets.” We can only wait and hope for the best.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Historically, Georgians have rarely ridden the wave of change, but we’ve shown a pretty good knack for not getting demolished when it breaks on the shoals of our collective stubbornness. I learned this firsthand in Eatonton and Milledgeville.

About a week after my 45th birthday I headed down with my friend Jim to see the Harllee Branch Plant, which lies on Lake Sinclair just north of Milledgeville, and then spend the day checking out the city and its various virtues. Jim suggested we drop by Eatonton as well. I’d never heard of the place, but Georgia, it turns out, is full of surprises.

To be continued…

The word week derives from a proto-Germanic word meaning “turn” or “move,” while the word fortnight derives from an Old English phrase meaning, in a characteristically (vis-a-vis the Old English) straightforward fashion, “fourteen nights,” so you tell me who’s being silly here.

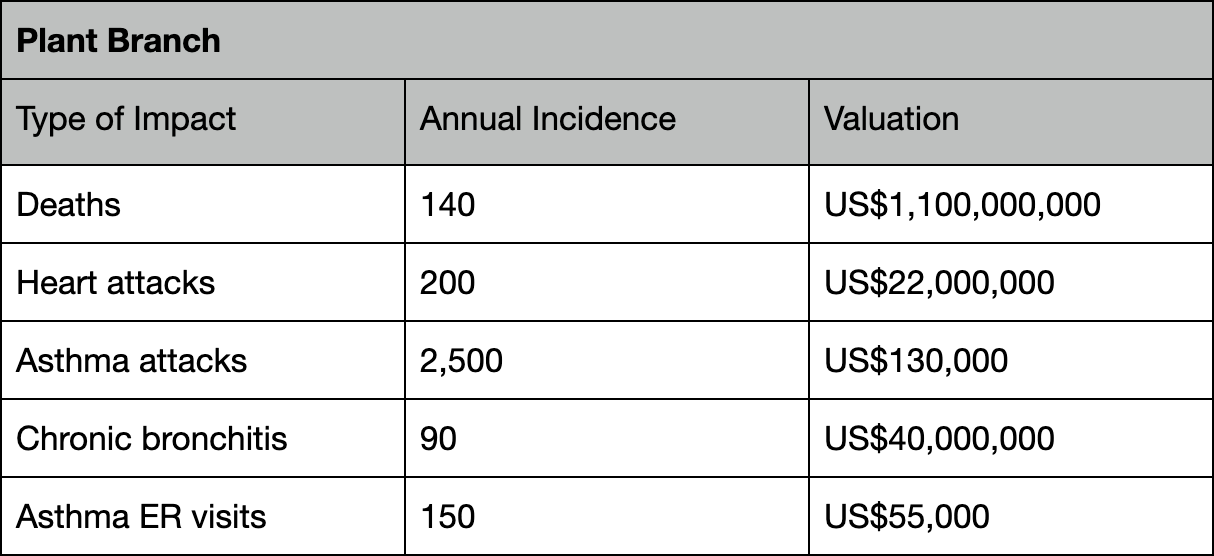

All impact data from Clean Air Task Force, http://www.catf.us/fossil/problems/power_plants (retrieved ages ago). Furthermore the data is all about seven years old and it’s quite probable that in the meantime the plants have all been closed and replaced with systems that run entirely on good intentions. If you’re relying on this piece as a source for your senior research paper, stop now and return to playing Fortnite.

For example, this plant was closed in 2019.

Holy crap: this plant was demolished in 2016! We did it! We did it! Ma, get Pa! We did it!