Dear reader, this is the second installment of my trip across Georgia to visit its various coal-fired power plants. If you haven’t read the first, you can find it here. You don’t have to read it—this is basically a travelogue, and you can join me anywhere. However, you’ll do better on the test.

We pick up the thread in Eatonton, seeking out the Harllee Branch plant.

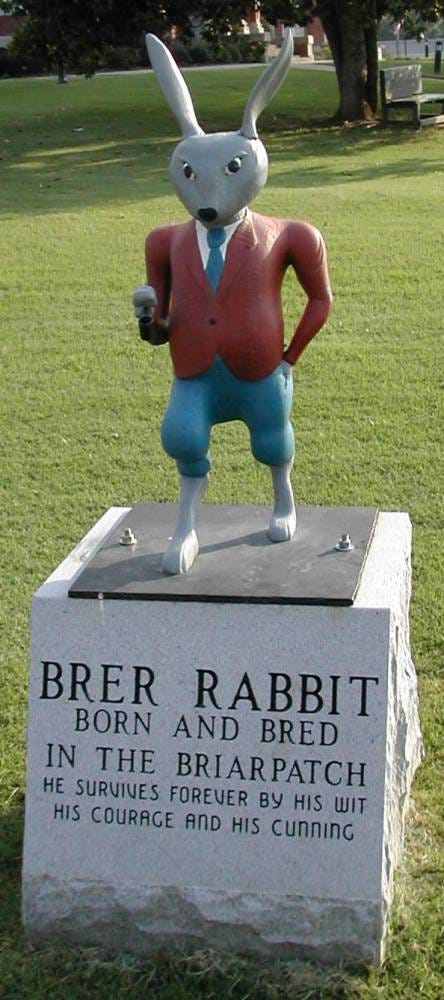

My experience with small town America is fairly extensive—gleaned in part from the long bicycle trips across the South and the Midwest I’ve taken every couple of summers for the past decade. Most of the small towns I’ve visited are open, festering sores, rife with poverty and decay. Keithsburg, Illinois, Hughes, Arkansas, and Normandy, Tennessee, to name a few, are highlights in a protracted litany of whistle-stops that have long since stopped whistling. So it’s usually a bit of a jolt to roll into a place like Eatonton, which is put together like a movie set of The South. The birthplace of both Alice Walker and Joel Chandler Harris, Eatonton wowed us right off with its immaculate and charming square, centered around a big brick courthouse, replete with a little statue of Brer Rabbit. It’s a nice whimsical touch — towns aren’t typically known as fountains of humor, but Eatonton makes an effort.

One is left scrapping for an explanation for Eatonton’s continuing virility, given the lack of any obvious signs of industry and the town’s remove from any significant thoroughfares. Indeed, we were accosted at one point by a woman asking if we could offer her a job—certainly an incident at adds with the town’s chipper appearance. Maybe they were just inordinately lucky—Billy Sherman skipped Eatonton on his fiery jaunt through Georgia due to rain. Rain!

Or perhaps it’s just tourism? Well, to buy that you have to buy the idea that large numbers of people are descending on the Uncle Remus museum and the Uncle Remus golf course and the Uncle Remus regional library system and, presumably, the Uncle Remus radiator shop and the Uncle Remus septic tank pumping service. Or perhaps the small, dusty room that houses the Georgia Writers’ Hall of Fame, filled with the work of people who, while indisputably artists of high caliber, suffer an ever declining relevance in a world informed by the vapid cult of celebrity. It was closed anyway—on a Saturday afternoon.

Of course, we went to the Uncle Remus museum. So there’s that.

Located just on the edge of town, the museum is a small, low building constructed out of the remains of two former slave cabins and a room from the Turner Plantation—Turner being the owner of the slaves whose stories Harris turned to publishing gold (I don’t know whether Harris ever gave anything back to the slaves, so I’ll withhold the snide remarks that bubble up even as I write these words). Neither of us had any great desire to pay the fee to tour the whole museum, so instead we chatted up the proprietor, a largish, obliging woman probably in her late 60s. She wound up showing us as much of the place as I could have expected had we indeed paid. Turner’s bizarre Lost Cause-propagating newsletter, some stills from Song of the South, translations of Uncle Remus books into Russian — we got the works, and all for the price of a little conversation.

Eventually we turned the subject to Plant Branch. She knew it well. Her father, she told us, worked there, and they lived nearby. She confessed that at the time she didn’t know anything about the health dangers of coal, but she remembered—this was presumably before the scrubbers were installed—having to keep a watch on the wind if you had clothes hung out to dry, least it change direction suddenly and cover the washing with soot.

I remarked that the plant was closing in 2015 and asked if she was glad to see it go.

“No,” she replied, “Coal fed me.”

It wasn’t feeding us, so we drove on, our arrival in Milledgeville heralded by the rumbling of my stomach. We found a place near the Georgia College campus and ate average food dolled up by hunger. Across the street was a beautiful old movie palace that had long since died and been reanimated by Barnes & Noble in the interest of selling astronomically marked-up textbooks to Georgia College students.

I could go on to say that I may have witnessed a girl shoplifting at the Milledgeville Army Surplus Store, but it would be stingy to dwell on the negative. Milledgeville is a lovely little city. It was the third of Georgia’s four capitals, the first being Savannah, the second being Louisville (with only ten years in the role, Louisville is the George Lazenby of Georgia capitals), and the fourth, of course, Atlanta.1 Milledgeville is unique in that it was built specifically to be a capital. Long about 1804 some atypically rational Georgians decided that the expanding state needed a more centrally-located capital, so they loaded up the governor and the legislature and all their various papers and hauled them to a tract of land they’d cheated the Creek Indians out of a few years prior. They laid out a grid of streets and erected an outlandish capitol building, and before you could say “filibuster,” Milledgeville was the king’s court; and remained so for sixty-four years.

We ambled around downtown for a while, visiting the governor’s mansion—said to be a paragon of the Greek Revival style, though such distinctions are lost on me—and the Milledgeville cemetery, where lie a parcel of significant Georgians, not least of which is Flannery O’Connor. We stood in the blazing heat for a while, looking at the place where her bones are interred. For a reason we never fathomed, the stone was covered with pennies.

On the way back to the car we embarked on a perplexing search for the Old Capitol building. The map placed it somewhere near the center of the Georgia Military College, but no matter how we approached it, one particular building always seemed to be in the way; at last we realized it was the building we sought. The structure is much more evocative of a castle than it is a capitol, and all the buildings of the college were designed to mimic its look, which two facts combine to produce an effect that is simultaneously militaristic and redolent of theme parks.

We opted to bypass the Capitol Museum, as the hour was growing late and we still had a number of significant items on the agenda. On the way out, however, we got to talking with a woman who was waiting for her son—a student at the prep school. She told us she’d lived in Milledgeville for only a short while, so we dropped the bomb, asking whether it bothered her that there was a coal plant only ten miles away disgorging toxins on her adopted city. She claimed to be aware of the plant but said that she’d never given it much thought. She also had a look on her face like she’d just been accosted by a couple Jehovah’s Witnesses. She was game about feigning interest, but my guess is that hers was no cost-benefit calculation; rather, the problem was simply out of sight and out of mind. I can understand that—modern life is a barrage of bad news. Problem is, the people making our energy choices for us count on this.

Central State Hospital, our next destination, is a microcosm of all that is right and wrong with Milledgeville, and indeed, the state, the country, probably the whole human race. On the surface it’s just this spooky, crumbling old mental hospital, born in the midst of a wave of reform in the early 19th century, which aimed to systematize prisons, hospitals, and public schools. While the reformers were driven by the most altruistic motives, that phrase—prisons, hospitals, and public schools—says a few ill things about their thinking. The bill that established Central State called for the creation of a “state lunatic, idiot, and epileptic asylum.” Clearly their prowess in the field of taxonomy leaves a lot to be desired.

Of course, there’s plenty about the burgeoning 19th century field of psychiatry that’s easy to mock in the here and now. But, just as the South is practically by definition an admixture of good and bad, here too one must acknowledge the complex history of this storied institution. Central State’s original leader, Dr. Thomas Green, was a humane man who helped move the penally-oriented psychiatric practice toward one with a medical character. And most significant to Milledgeville, the hospital would prove a savior for the city when the government removed to Atlanta in 1869. For many cities this would have been a death knell, but Milledgeville successfully weathered the transition. The hospital, along with the two colleges—both formed in the wake of the government’s departure—played a large role. The coal plant served similarly in the 1970s when the hospital was on the wane.

None the less, there’s something pretty disgraceful about the manner in which Georgia designated Milledgeville as a dumping ground not just for the mentally ill, but for fringe members of society. In spite of the good the hospital did, it was also a convenient tool for dispensing with those perceived as undesirables—indigents in particular. So effective was it at scouring the weird and wanting from Georgia society that it became a prototypical threat to misbehaving children, and Milledgeville itself became a shorthand for this peril. “Go to bed or we’re going to send you to Milledgeville.” No doubt the city laughed all the way to the bank about that one, but the fact remains, we—people in general—seem to have a well-developed faculty for externalizing everything we find distasteful, be it epileptics or sulfur dioxide.

Our last stop was Andalusia Farm, where Flannery O’Connor wrote most of her fiction during the last 15 years of her life. Andalusia is a picturesque and peaceful place. At 550 acres, the farm is an oasis in the midst of the edge city that surrounds Milledgeville’s bright core. Flannery would probably puke if she could see the view across the street from the place today, but at least within its confines very little has changed since 1964. Even her bedroom is pretty much as she left it, right down to her record player and a small stack of Bach and Beethoven LPs.

Visitors are expected to self-guide, but we managed to extract a pretty fair bit of information out of one of the attendants, a bookish but vivacious woman in her late twenties. We must be charming. Naturally, we turned the subject as quickly as possible to Plant Branch. Her response was unusual; she was keenly aware of the damage the plant did, but she was unwilling to celebrate its immanent closure.

“I know it’s bad,” she said, “but I know people that depend upon it for a living.” Southern deference to one’s neighbors.

We saw the plant itself twice that day, coming and going. It’s hard to miss. Situated alongside the major north-south thoroughfare, it’s almost impossible to get to Milledgeville from Atlanta without driving right past it. All of the coal plants in Georgia are neighbored by water of some sort, but Plant Branch was the only one I saw that combined the two in such a dramatic and jarring fashion. Lake Sinclair was created when Georgia Power dammed the Oconee River in 1953 for a hydroelectric station. The lake is a major draw for boaters and fishers, who in turn provide another pillar of support for nearby towns like Milledgeville and Eatonton, demonstrating once again how nothing here is unalloyed. Hell, Flannery O’Connor probably went boating there.

Of course, hydroelectric didn’t provide enough power to supply the state’s growing energy maw, so in 1965 Georgia Power popped in a new generator and began burning coal. We stood and looked at it from a boat ramp surrounded by picnic tables and festive umbrellas. The contrast between the party-friendly atmosphere on our bank and the roaring vulgarity that filled the sky just a couple hundred yards away was something that Hieronymus Bosch would probably dismiss as fanciful. As if to drive the point home, we watched while a tiny deck boat motored back and forth among some small islands near the far shore. A man covered head to toe in a white protective suit and a respirator would periodically exit the jaunty little boat to spray chemicals on the weeds there.

The contrast isn’t just physical though. It’s imprinted on the people that are the children of the plant. Milledgeville and Eatonton are survivors. They’ve survived war, weather, demographic and economic catastrophes. Like Brer Rabbit, they do it with wit, cunning, and courage. And after all, what could be more cunning than coal?—a trick for turning a brittle black rock into light and power. Phenomena which have been scarce for 99 percent of human history are now taken for granted.

Conversely, the harms they produce are unlike any that people have seen before. A million years of evolution prepared us to deal with immediate, visceral threats like lions and bears (and Brer wolves); they taught us nothing about carbon dioxide and its slow interaction with the kinds of forces that aren’t even perceptible without keeping a log. It’s that Faustian bargain again—the Devil’s charge is never quite clear until it comes due.

Fried Green Coal

For a couple of years when I was a kid, I was mad for model railroads. I had a four by eight sheet of plywood out in the garage where I worked on my layout when the Michigan weather was warm enough. In the quiet of our rural home, the occasional passage of a great long train on the rails that lay on the other side of the highway was a big entertainment. They often consisted of well over a hundred cars, and never failed to draw me from the house to wave at the engineers up front and in the caboose. I spent my weekends and the meager funds I earned mowing the lawn at the Aardvark Hobby Shop in Clare, and the best day of each month was when the latest issue of Model Railroader arrived in the mail.

It never would have occurred to me, at eleven, that the map is not the territory. At 1:87.1 scale, it’s hard to portray human activity at any but the grossest level of detail. You wind up with a lot of workers hauling logs around, driving earth movers, maybe lowering concrete blocks into place. Domestic and recreational life consists largely of people walking dogs, children holding improbably large clusters of balloons, perhaps a boater navigating a polyurethane river. And even these sorts of things are just tiny ornamental details. At its core, it’s a hobby devoted to the celebration of large-scale, mechanized human endeavor. What you won’t see are intimate expressions of love, joy, humor, anger, pain...

It never once occurred to me to model a hospital with an oncology ward full of people stricken by years of breathing coal dust from passing trains. I probably would have been a good candidate for therapy if I had—I was a kid, and it was a hobby. But my experience with little plastic and metal engines and cars undoubtedly produced a model in my brain; a certain model of industry and its place in the American experiment. And in a lot of ways, that model is still there to this day.

One Sunday in late October I piled the family in the car and drove them to Juliette, Georgia, a railroad town with roots stretching as far back as 1839. The town was named for the daughter of a railroad engineer, Juliette McCracken, which may give you some hint as to the significance of the place in the grand scheme of history. Anyway, the boom years came during the first half of the twentieth century, when Juliette was dominated by a grist mill and a cotton mill. For a while, it was worthy of its dot on the map; its amateur historians claim the grist mill to have once been the largest in the world.

Of course, grist milling isn’t exactly a going concern these days, and indeed by the mid-60s, the town was already on the point of being completely swallowed by kudzu. And then Hollywood showed up.

Fried Green Tomatoes was shot, in part, in Juliette in 1990, and gave birth to a flourishing tourist trade. For decades the film’s Whistle Stop Cafe had in fact been an empty hulk, but smelling money the owner refurbished it and now you can go enjoy fried green tomatoes for yourself in a rustic environment clearly intended to convince the weary traveler that she’s imbibing a slice of history. It isn’t really any such thing, but the tomatoes are pretty good. The rest of town is in the same mold. The Chicago Times’ review of Fried Green Tomatoes could just as easily be a review of Juliette itself: “The movie never quite shakes its stiff, studied feel, just as the town of Whistle Stop never stops seeming the quaint creation of an art director.”

When we left the interstate, however, we were not immediately greeted by Kathy Bates in drag. The first thing that catches your eye on Juliette Road is a gargantuan concrete edifice that is so alien to the surrounding landscape that it wouldn’t be surprising if it suddenly lifted off the ground and rode a set of rumbling rockets into orbit.

This would be Plant Scherer, the largest carbon dioxide emitter in the U.S. Scherer stands apart from its brethren—it’s the fifth largest in the nation for one thing. It was the first active one I’d seen, and it was the first I’d seen with cooling towers. Cooling towers have become emblematic of industrial disaster, though they are among the more anodyne elements of a power plant, being in essence just saucepans full of hot water. That’s not to say that they are without hazard, but the dangers are pretty pedestrian. Fog. Icing.

What you won’t see at Plant Scherer, at least not unless you can get past the security guard at the front gate (who told me there was nothing to see but steam anyway) is the coal pit. The plant’s fuel is stored in a massive, oval-shaped pit. Google Earth and my half-assed math tells me the pit, at almost a half mile across, covers something like three million square feet. That’s a lot of feet! And a hell of a lot of coal. The pit is circumscribed by a rail line, and anywhere from two to five times a day coal trains comprising up to 120 cars roll past the oval and drop their cargo into the pit. It boggles the mind.

And of course, every one of those trains pass through Juliette, within a stone’s throw of the Whistle Stop Cafe. At over a hundred tons of coal per car, that’s between 24,000 and 60,000 tons of coal every day, barfing up clouds of dust as they pass like Pigpen from Peanuts, except that every particle of it has the potential to put you in the hospital.

“It’s a blessing and a curse,” said the proprietor of a little antique shop across the road from the Whistle Stop, one of the many small tourist-oriented businesses that have sprung up in the shadow of the cafe. Scherer is undoubtedly a big economic mover for the nearby city of Forsyth, and probably for Juliette to some degree as well. It was this very prosperity that drew her to Juliette from northern Nevada five years ago. But even so, she was unequivocal—she wanted to see the trains stop.

“People think I’m crazy. I’m the only Democrat in Juliette,” she laughed. I can sympathize—if you haven’t yet divined my political inclinations then you need to get a new dowsing rod. But it’s frustrating to see partisanship colonizing either side of this issue like superpowers backing third-world countries. “Conservative” shares a root with “conservation,” but it’s nearly impossible for someone like me to make that point, because apparently “liberal” shares a root with “Satan.”

But she told me something that gave me a glimmer of hope. Her father, she said, was a lay minister at her adopted church. One of his first sermons was on environmental stewardship—a subject you might assume would not be terribly welcome in a small Georgia town like Juliette. But he told everyone to wear their camo. That in itself is a point, in a manner of speaking. And a good one. Camouflage is made in the image of the wilderness; not concrete, not coal, not passing trains.

Shortly before we left Juliette I saw a train myself. It stirred in my spirit the same admiration I’d had as a boy, but now I know more than I did then. It didn’t seem particularly dusty, but as usual the statistics on asthma and other respiratory illnesses bear out the invisible damage. I watched it go past from the porch of the Whistle Stop. A few yards in front of me a woman dressed in her Sunday best kneeled next to her two children, whose blinding blond hair stood out in stark contrast to the gray train cars.

They waved to the engineers.

Hope you enjoyed stage two of my long, ludicrous trip. The third, and last, will probably come in September, when I’ll be taking a month-long break from writing to eat muscadines. The surprise I’ve been teasing you with for months now is probably coming in September as well; perfect timing given that I’ve been at this for almost ONE YEAR. Amazing, isn’t it?

Cheers!

It’s unlikely but possible that some among you will be aware that Washington, Georgia was also the capital, but only for a vanishingly brief period during the Revolutionary War and thus may not count. I don’t know the rules.

Your blogs have me all fired up. Ha ha. Ha ha ha! HA HA HA HAFFGHHHHGHHH...<wheeze...> CHHHHGKHKKLGHH...<spit>