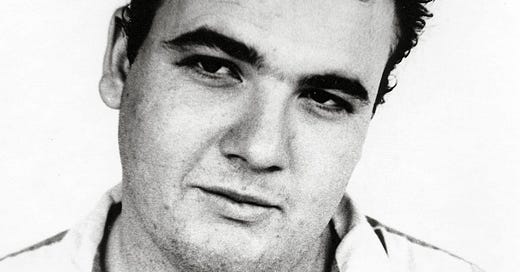

I discovered the Minutemen sometime in the summer of 1986, maybe six months after D. Boon, their 27-year old singer and guitarist, was thrown through the back doors of their van when its rear axle broke and it flipped twice on I-10 in the Arizona desert. He died instantly.

Everything you need to know about the brief but bright candle of his life is encapsulated in the title track of the Minutemen’s first full-length album The Punch Line, released on All Saints’ Day 1981 when I was a twelve-year old doofus residing with my grandparents in the hinterlands of Michigan without a clue that they even existed, or that there was music in the world beyond what was aired on Hee Haw each week. The song is a razor blade:

I believe when they found the body of General George A. Custer

Quilled like a porcupine with Indian arrows

He didn't die with any honor, any dignity, or any valor.I believe when they found George A. Custer

An American general, patriot, and Indian-fighter

He died with shit in his pants.

I can understand if you think this is juvenile, but eviscerating lazy American myths is serious business in my opinion. I love it for three reasons:

The raw, spare, brawny language—Custer isn’t just stuck full of arrows; he’s quilled with them, like a porcupine. The Minutemen were crude, but they possessed a literary heart.

The ludicrous brevity of the song; 24 of its meagre budget of 41 seconds are spent on introductory music, after which Boon appears, voice like a belt sander, roaring the lines over ten repetitions of a two-bar phrase in the bass and drums. And then, like a brick through a window, it’s over.

And finally, the juxtaposition of the sublime with the ridiculous. “The Punch Line” is absurd in almost every way it could be—it’s absurdly short, absurdly offensive; from a musical standpoint it’s absurdly constructed. But Boon and company were definitely not kidding around. The punch line isn’t just the end of the joke, it’s a fist to the solar plexus.

Custer has lost some shine over the past forty years, but in 1981, the paleoconservatism epitomized by creepy organizations like the John Birch Society and the Moral Majority was clawing its way toward the mainstream, led by the grinning skull face of Ronald Reagan. Reagan gave racism and greed a sunny disposition, but the revolution he led would shortly metastasize into the party of Newt Gingrich and the pinch-faced, zero-sum politics we suffer under today, so you know what? Fuck that guy.

Anyway, Custer was a White military officer whose late career centered around brutalizing and decimating the indigenous population, and was thus a holy American hero. Perhaps not a name on the tip of everyone’s tongue, but revered among a certain set. Taking a dump on his reputation was a perfectly sensible way in 1981 to thumb one’s nose at Reagan’s nascent race-baiting, dictator-propping, oligarch-fellating regime.

Only two of the eighteen songs on The Punch Line require more than a minute to unfold, and the longer of those clocks in at a minuscule one minute and twenty seconds. This led a lot of folks to assume that the Minutemen were the Minutemen because their songs were all a minute long, but this was not a band prone to gimmicks. They chose the name in reference to the original Minutemen of Concord and Lexington—a ready force dedicated to liberty and revolution, and likely the reason the Atlanta Journal Constitution erroneously described them as “from Boston.” The bulk of their catalog of four albums and nine EPs framed pointed arguments against American imperialism, especially regarding South America. I didn’t fully grep the depth of the politics but I liked the tough, angry anti-Establishment sense of it all. Boon was a man of little formal education but an incisive mind and he ripped through the decadent insouciance of the world around him with crackling energy, wicked humor, and infectious wrath. In the last decade or so many of us have been asked for the first time to check our privilege, but nearly forty years ago Boon1 was already asking:

What of the people who don't have what I ain't got?2

Are they victims of my leisure?

And, because this was the Minutemen and not a bunch of humorless red-faced bores, he necessarily concludes,

Maybe partying will help.

The Minutemen arrived in my ears courtesy of my friend Aaron, who was the conduit for pretty much all the music I learned about in my mid- to late-teens. I don’t know by what black magic he found such wondrous, alien things, but he inundated me with his discoveries, so I owe him a debt of gratitude. So it was that one day in my 16th year Aaron pulled a record out of a white cardboard sleeve bearing a hand-drawn image of two men, Boon and bassist Mike Watt, shouting in each others’ faces while various debris—a watch, a shoe, a telephone, to name the more easily identified items—sail through the space between them. Demons observe the proceedings from the bottom of the fame, and below them is printed the long and unwieldy title: Buzz or Howl Under the Influence of Heat.

The album begins with the crack and clatter of drums, a tinny guitar spewing a froth of lo-fi funk, and a loud, snappy midrange bass guitar outlining an anxious, off-balance lick. I can quote “Self-Referenced” for you in its entirety because it’s only seven lines long:

Burned-out wreck spotted on the beach

Symbol for my life

How can I believe in books

When my heart lies to me?

I'm full of shit!

I'm bummin' real hard on cold steel facts

Full of shit!

I was hooked immediately. This music was weird, it was subversive—hell, with its bizarre nods toward funk and jazz it even subverted the punk rock milieu from which it sprang—and it had a sailor’s tongue but a writer’s brain. To me it was perfect, both as music as well as a blueprint for how to do things: how to think, how to live an authentic life. I copied the album to a cassette tape, along with The Punch Line; the twenty-six songs of two albums together comprised a mere thirty minutes of music. Subsequently I devoured the rest of their catalog, listening to it so frequently that I still mentally register the stretches and warps that developed in the music as the tape wore out, but it was a long while before I learned that they were already gone.

Information traveled slowly in 1986, and by means that are mystifying to me in retrospect. Maximumrocknroll was pretty much the only definitive source of punk rock news at the time, but issues of the San Francisco periodical were as rare as saints’ relics in Nashville. Everything else came from liner notes or rumors spread by random kids at the five-buck all-ages shows that popped up most weekends at clubs like the mysterious, sprawling Cannery or the claustrophobic little box known then as Elliston Square. We gathered what scraps of news we could like we were panning for gold, carefully committing every established or semi-established fact to memory and interpolating the gaps as best as we could. Information was valuable then. Now it’s like a colossal toilet backing up everywhere all at once.

Around 1993 I did a little experiment: for one year I would only listen to classical and jazz music. Don’t ask why—I’m not entirely sure myself. My son’s best friend, a 14-year old from a non-religious family, is plugging his way through the King James Bible. Kids do odd things.

One year, however, turned into almost ten. I basically missed the 90s, at least as far as rock and roll was concerned. I got married and we moved to Boston, where, at the conclusion of the decade I found myself working as a junior designer in several early online advertising agencies. We made animated banner ads mostly, so if you’d like to know who to blame, I’m your huckleberry.

At one point I was housed in the office of another designer who was absent on some sort of sabbatical, and lined up along the back of his desk were several dozen CDs—Hüsker Dü, Black Flag, Minor Threat, Sonic Youth, and yes, the Minutemen. I couldn’t resist their magnetic pull, so desperate was I for relief from hour upon hour of shifting images of Ford pickup trucks back and forth in little rectangles. So I plunged back in with nostalgic fervor. For a couple years thereafter I wallowed in the music of my youth and began to fill the gaps I’d incurred from my Tchaikovsky experiment. Some things passed the test of time, some didn’t. The Minutemen were as intoxicating as they were the first time I’d heard them.

In 2005 I moved with my wife and daughter to Atlanta, where I started a job cranking out websites for Georgia Tech. In a small stroke of irony, I discovered that the Minutemen’s final tour, in support of R.E.M., had concluded in the fall of 1985 with two dates at Atlanta’s Fox Theater—a venue into which they probably never would have been admitted without the good graces of Michael Stipe and company—and while they were in town they stopped by Tech to perform a 90-minute set at the student-run radio station, WREK. The performance was eventually uploaded to YouTube and while it probably wasn’t their last gig, it has the virtues of being both available and well-recorded. They sound as tight and muscular and energetic as I’ve ever heard them. Three weeks after that, Dennes Dale Boon was dead.

I’ve never had the opportunity to mourn the loss of Boon. He preceded me, at least insofar as his musical life and mine go, as much as did Jimi Hendrix and Janice Joplin and John Bonham. Like them, he is to me something other than just a great musician. His bandmates, Watt and drummer George Hurley, went on to form other bands and record other albums. I like them, but they can never be what Boon is. D. Boon is a mythical hero, a colossus with a guitar and a microphone, a man who will remain ever younger than me but oh so much wiser. He emerged from the humble navy housing of San Pedro, California while I was taking guitar lessons from a tedious old man who had me playing “Yankee Doodle” for literally a month. In the space of half a dozen years he bombed around the country and the world like a loose firehose,3 and then he vanished while I was still stumbling over the chords to “Bad Moon Rising.” He left barely a trace beyond the hundred-odd puzzling little songs that were his life’s work, but each of those worked on me like a spell.

“Our band could be your life.” This line, from the song “History Lesson – Part II” off their double-album Double Nickels on the Dime is probably the most famous Minutemen lyric,4 as it has been pressed into service as the title of a D. Boon tribute album, a book on punk rock in the 1980s, and a course offering at the College of the Atlantic.56 It’s a pretty good line, insofar as it’s an argument for doing something with your time other than vegetating to a Friends marathon. For my money the best Minutemen lyric comes from “Political Song for Michael Jackson to Sing,”7 off the same album. It’s a Watt lyric, but it is incomplete without Boon’s guttural bellow. I think of it as a sort of primitive call to mindfulness:

If we heard mortar shells

We'd cuss more in our songs

And cut down on guitar solos

Of course, D. Boon and the Minutemen were always pointedly aware that they didn’t hear mortar shells—that’s long been a privilege of being White and American—so with their iconoclastic humor and deadly seriousness of purpose, this trenchant observation is followed by what else?

A guitar solo.

If you are as smitten with D. Boon as I am, or even if you aren’t, please like and comment and share and all that shit. I feed my kids the love I get from y’all and they’re pretty pissed about it, so probably we all need to amp it up a notch. As always, thanks for reading.

Disclaimer for those who will tell me Mike Watt wrote a lot—maybe most—of this stuff: I know, but ask yourself whether you think of Paul Schrader or Robert DeNiro when someone says, “I am God’s lonely man.”

I’ve never understood the double-negative either, but since it’s from a double album called Double Nickels on the Dime I think we can just stipulate that we’ll take as many of those as we need to reach the obvious sense of it.

A fIREHOSE, for those of you in the know.

The intro to the song “Corona” was fated to serve as the theme music for Johnny Knoxville’s Jackass television show, but few who hear that classic lick will ever hear the lyrics or go on to learn that the bouncy country-rock tune is about the frustrated helplessness of an American tourist who meets a poor Mexican child on the beach and is unable to provide anything to her other than a Corona bottle, worth five cents for the deposit.

I know this because my daughter will be attending COA in the fall and I have pored over the catalog with a mixture of admiration and jealousy.

I haven’t yet convinced her to take the class, but I will.

The Minutemen actually sent this song to Michael Jackson in hopes he might perform it, but sadly he never did.

Thanks for this excellent trip back to college days. These guys said a helluva lot in a few succinct lines.

I remember my little brother playing "Buzz or Howl" for me (I was a hippie and he was a hardcore LA punker 7 years my junior - the other song he introduced me to was Slayer's "Chemical Warfare") and I was hooked.